An Olympic Dream?

Villaggio ENI — Cortina's Modernist Mountain Utopia

This story is an update of an earlier piece on Cortina and Villaggio ENI. It was published in Dutch by Knack Weekend en in French by Weekend Vif

In 1956, the world arrived in Cortina d’Ampezzo to watch Italy’s historic comeback. Cameras rolled in on new roads, the ammonia-cooled ice glittered under the floodlights of the stadium, and the Winter Games were broadcast live across Europe for the first time. A once-in-a-lifetime investment that cemented Cortina’s ‘Queen of the Dolomites’ crown.

Seventy years later, cranes and temporary grandstands are back for Milano–Cortina 2026: the same valley, but a very different idea of progress. Just behind the TV cameras, a social journey began that would outlast the Olympic fortnight.

While Toni Sailer skied to gold on the slopes above Cortina, a few kilometers south, in Borca di Cadore, another Olympic-era project was rising. It had no medals, no sponsors’ banners, and no television coverage. It had something rarer: a CEO who wanted to build a utopia for his workers.

Enrico Mattei had a knack for making enemies—powerful enemies.

In the end, it got him killed.

His rise from humble beginnings to one of Italy’s most influential post-war figures was meteoric and contentious. Mattei was a man of contradictions: a shrewd industrialist with utopian ideals, a corporate leader with an eye for the social good. As CEO of ENI, Italy’s national energy giant, he dragged his war-torn country into a new modernity, carving a place for it among global powers.

He wasn’t known for subtlety: he broke the oligopoly of American oil companies, negotiated energy independence for Italy, and openly meddled in geopolitics, from the Middle East to North Africa, backing Algeria’s liberation from French colonial rule.

His enemies called him a rogue. His admirers, a visionary.

Mattei’s plane never landed at Linate Airport that October night in 1962. It disintegrated. Lowering the landing gear triggered a hidden bomb. It was a shadowy, cinematic end to a man whose ambitions had touched every corner of post-war Europe. Yet Mattei’s vision was not just industrial or geopolitical. It was cultural.

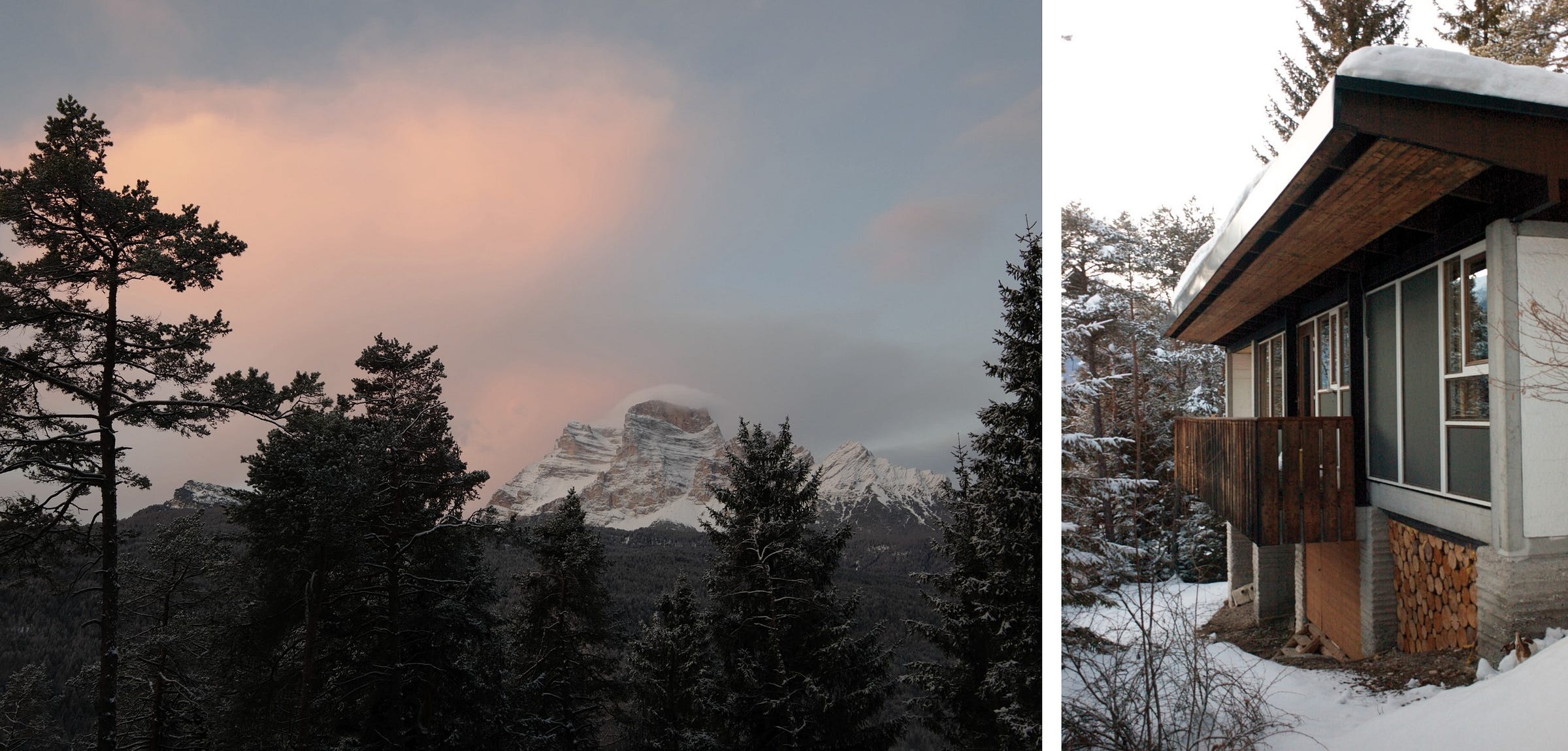

Nowhere does it survive more poignantly than in Villaggio ENI, a modernist utopia nestled in the Dolomites near Cortina d’Ampezzo.

When Cortina hosted the 1956 Winter Olympics that showcased Italy’s rebirth, ENI was part of that same narrative: a state-backed giant proving that the country could stand on its own feet, underwriting the very idea of mobility and abundance that the Games were selling. Its logo followed Italians along the roads and into the mountains, a promise that the future would run on domestic energy.

Villaggio ENI was the quiet, off-camera counterpart of that spectacle: if the Games were Italy’s shop window to the world, Borca di Cadore was the backstage where the new Italian middle class was being rehearsed. Not for two weeks of competition, but for a new way of inhabiting leisure and the landscape.

At Borca di Cadore, where Monte Pelmo rises pink and radiant in the morning sun, Mattei’s vision endures, subtle but unmistakable. His industrial empire was built on the labor of thousands, yet he insisted on seeing his workforce not as a hierarchy of executives and laborers but as a single collective. In this vision, Villaggio ENI played a central role. Conceived as a company retreat, it was not a luxury reserved for managers but a shared space for all ranks.

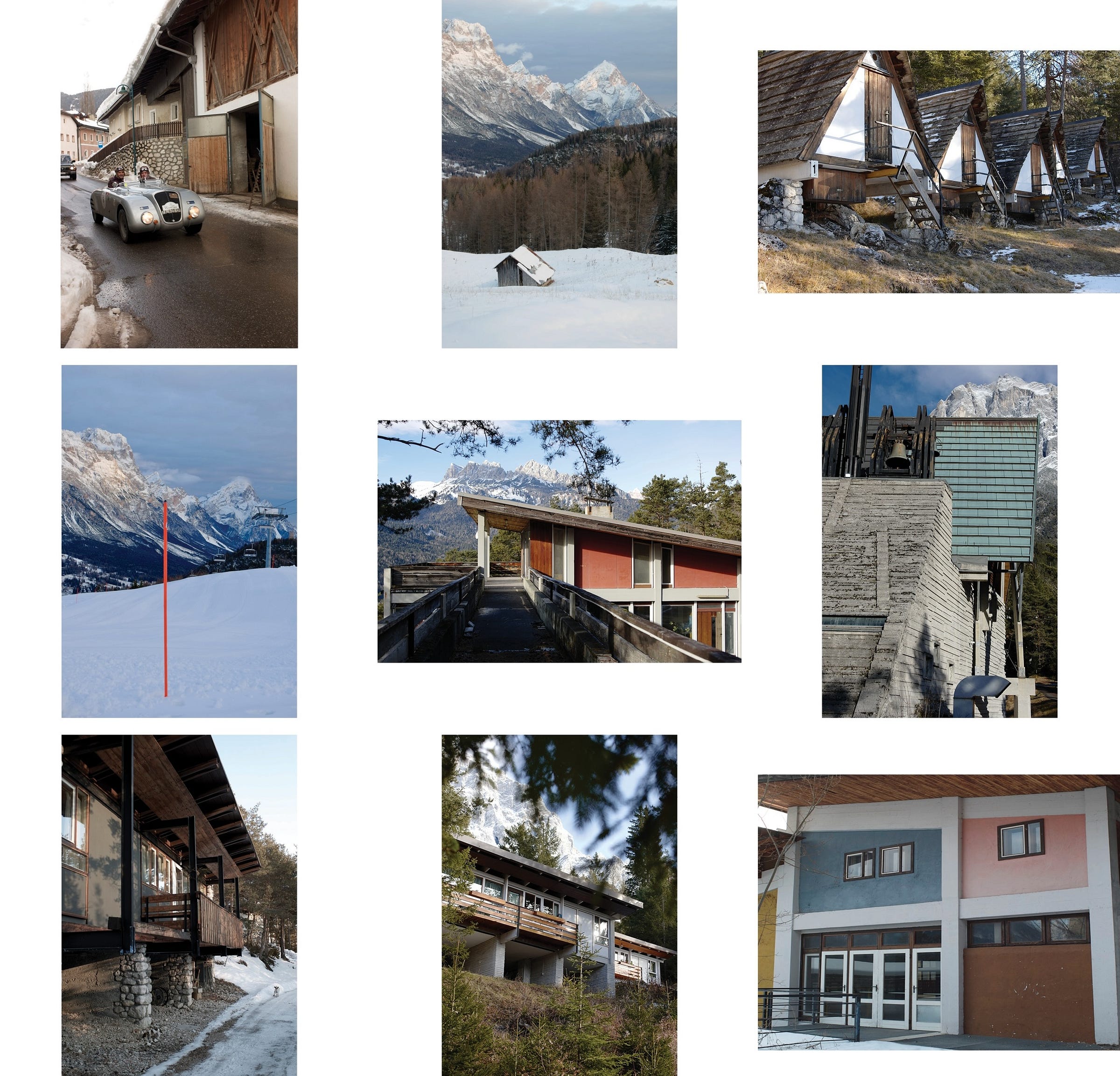

Here, workers and executives spent their holidays side by side, staying in identical chalets, studios, or hotel rooms, equal in size and design. Traditional markers of social class were deliberately erased, and in their place was an egalitarian community where families would meet at the same bar, share pews at the same church, and enjoy a lifestyle shaped by the innovations of Italian modernity: Agip fuel, Vespa scooters, Fiat 500s, and the buoyant optimism of a post-war renaissance.

To build this utopia, Mattei needed an architect who understood not only form but purpose.

Enter Edoardo Gellner.

A pioneer of modernism and architect of the Agip motel in Cortina, the concrete-and-timber gateway built for the 1956 Winter Games, he had already helped redraw the town for its Olympic close-up. His hand is still visible in Cortina today: in the Palazzo delle Poste and the adjoining Telve telephone building in Largo Poste, designed for the Olympic boom and recently restored, and in Ca’ del Cembro, his own house-and-studio perched above the valley, a laboratory where he first worked out his new alpine language. By the time Mattei called, Gellner was no longer just an up-and-coming architect; he was the man who had already rehearsed a modern, Olympic Cortina in built form.

He approached Villaggio ENI in the same spirit as the Bauhaus architects. His work here was a “total design” project, encompassing urban planning, architecture, interiors, and even the smallest details of furniture and fittings. He envisioned a community that would encourage spontaneity and interaction. The chalets, built in modular clusters across the landscape, created intimacy without isolation. Communal spaces—the bar, the church, the tabacchi—were carefully placed to serve as natural gathering points.

The chalets perch amid pine forests like angular sculptures. Through the south-facing windows of their minimalist frames, the Dolomite scenery bursts forward—raw, majestic, and intrusive. These were homes designed not to tame nature but to showcase it, as if to remind visitors of their humble place within its grandeur.

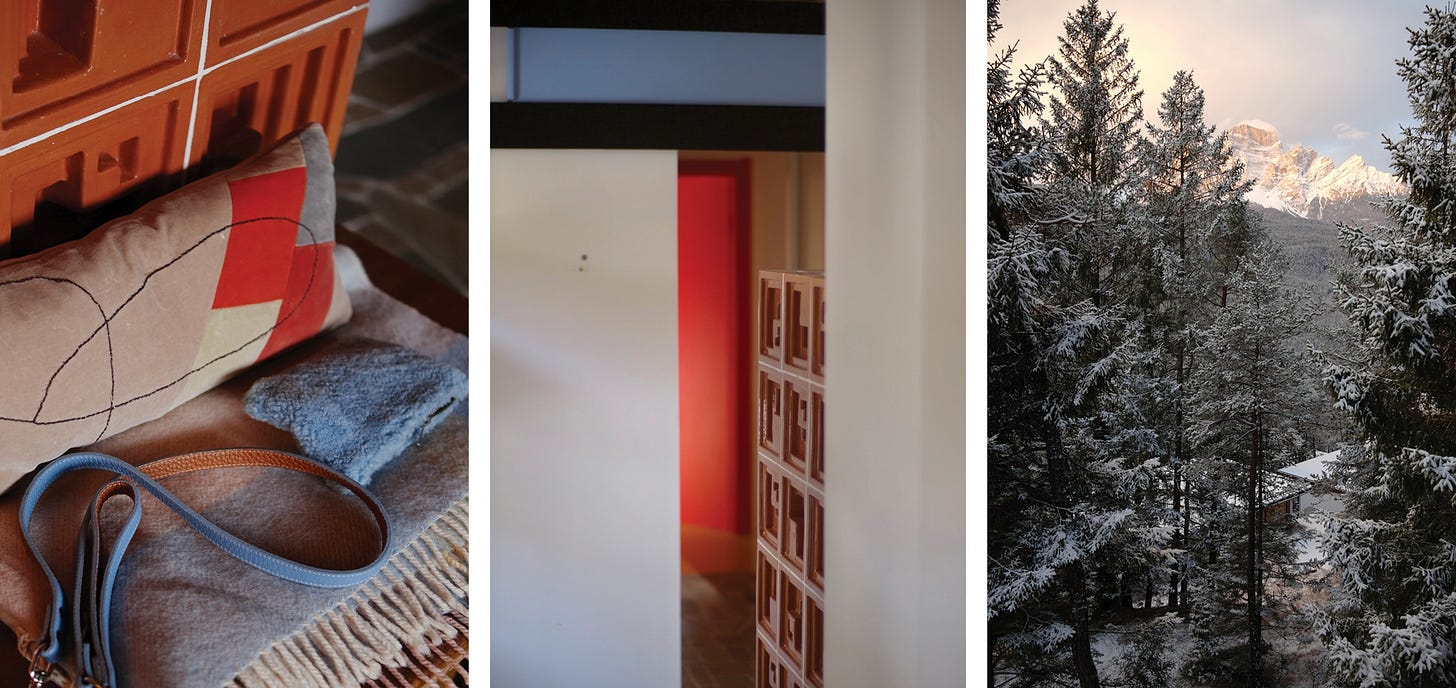

Inside, the contrast with the setting is striking. Bright yellow concrete floors play against blue and red walls, vibrant Formica kitchen worktops, and furniture of disciplined simplicity. Gellner’s designs speak to a harmony of contrasts—the bold and the serene, the natural and the man-made. His architecture was radical for its time. It rejected the heavy, ornate traditions of Italian Alpine design and replaced them with an unapologetic modernism: angular forms, sloping pent roofs, and minimalist interiors. His materials were local and honest—stone, timber, and concrete—and his palette restrained, save for those few, shocking patches of color. In 1956, when the first chalets were completed, the effect must have been disorienting—an alien landscape of geometric structures set against the jagged Dolomites. Yet, to those who stayed there, Villaggio ENI offered something visionary: a model for a new Italian way of life.

Villaggio ENI was more than a design triumph. It was a social experiment: a company resort reimagined for the modern age, shaped by the same post-war optimism that powered Cortina’s Olympic dream.

But time has not been kind to this ideal.

What the 1950s called progress, we now rebrand as heritage and then rebuild it as if nothing had changed. The sliding track above Cortina is being reconstructed for 2026 at a cost of over a hundred million euros, in a valley with less and less reliable snow and under a sustainability label that convinces few. The construction site for the new track has swallowed the old Bob Bar, where locals once ate porchetta sandwiches.

Down in Borca, Mattei’s idea of legacy—modest chalets for families, a church, a summer camp for children—has quietly been hollowed out by second-home speculation, their interiors gutted and replaced with IKEA furniture. The bold colors have faded, and windows hide behind laced curtains. The bar and tabacchi, once the heartbeats of community life, have closed. Without its original purpose—to foster connection and equality—the architecture has become a quiet monument to an idea that failed to thrive.

Some chalets have been bought by design enthusiasts and remain perfectly preserved.

The church still stands as the crowning jewel of Villaggio ENI. Gellner brought in Carlo Scarpa, his friend and mentor, for the design. Its stark yet commanding form rises from the mountainside like a solemn sentinel. Inside, light filters through narrow slits, illuminating bare concrete walls and wooden beams with a reverence that feels almost sacred. Religious services are infrequent, but the structure remains open for occasional events. Its presence is indelible—a reminder of what Villaggio ENI was meant to be and what it could never fully become.

When the world tunes in, Cortina will look different. The cameras will linger on the rebuilt sliding track, the refurbished ice stadium, and the branding draped over the Tofane grandstands at the women’s downhill races. Press releases will talk about sustainable investments, regenerated infrastructure, and a future-proof mountain economy. For a few weeks on air, the valley will once more be a showroom for whatever version of progress we currently believe in.

Borca will not feature in that story. The village will sit where it always has, half-asleep among the trees, its geometry softened by snow and lack of care. Some chalets will be perfectly preserved, others strangled by PVC windows. The church will open occasionally; Gellner’s colors will keep fading beneath laminated flooring. Villaggio ENI will not read as a triumph. It will read as a question.

Mattei’s dream was both naïve and serious. Naïve in its faith that a benevolent corporation could engineer equality with architecture and holiday bonuses. Serious in its insistence that workers deserved beauty, time off, and a place in the mountains that wasn’t just a backdrop on a postcard. That insistence still matters.

Design can set the stage. It doesn’t guarantee the performance.

The Olympics will come and go, as they always do. The sliding track will age. The slogans will be out of date by spring. But somewhere in Borca di Cadore, the pink morning light will keep spilling across a yellow concrete floor, catching the edge of a built experiment that never quite worked and still, stubbornly, refuses to disappear.

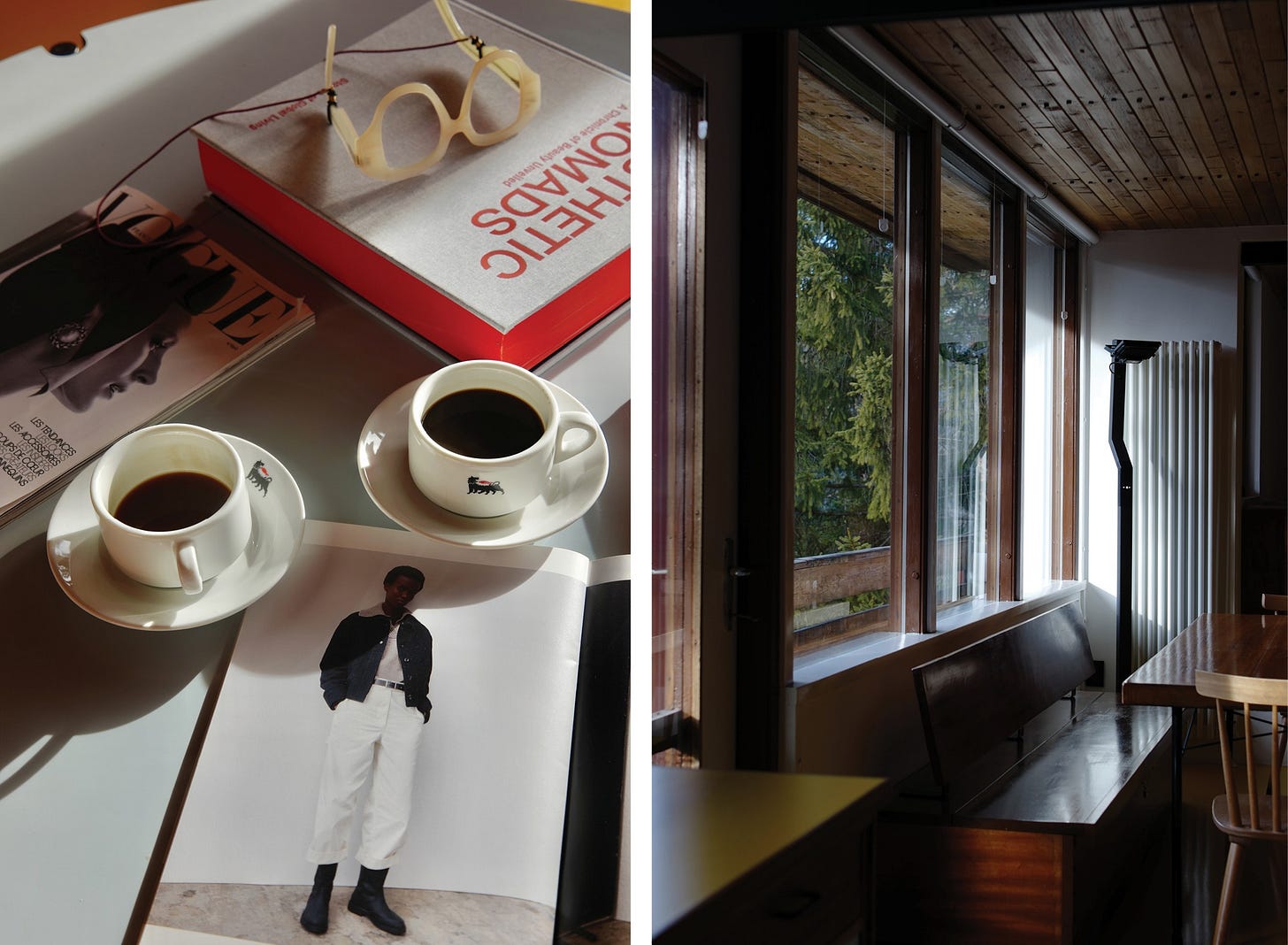

https://www.aestheticnomads.com/

THE ÆSTHETIC NOMADS BLUE BOOK: CORTINA

LA COOPERATIVA DI CORTINA

Founded in 1893 as a consumer cooperative, this remains the department store on Corso Italia. It is the town’s great equalizer: everyone shops here for an eclectic mix of local cheeses, car batteries, thermal baselayers, or the latest novel by Paolo Cognetti. You walk in wearing ski boots or your newest fur coat; nobody blinks.

Corso Italia 40

coopcortina.com

EL BRITE DE LARIETO

Dining happens right next to Nanda and Flavio’s dairy cows, high above the valley floor. Riccardo Gasparini crafts the menu strictly from the farm’s own produce, offering an authentic agricultural experience. He also commands the kitchen at the sister restaurant, San Brite, which has since secured a Michelin star.

Località Larieto

elbritedelarieto.com

ENOTECA CORTINA

Come 6 PM, it is standing room only at this institution, the town’s definitive wine bar since 1965. Elegant regulars catch up over a glass of dark Lagrein or a crisp Sauvignon Blanc from Manincor. The house-made tramezzini are non-negotiable.

Via del Mercato 5

enotecacortina.com

RIFUGIO DIBONA

From the entrance of the Natural Park, it is a two-hour hike up to this rifugio sitting beneath the looming Tofana rock face. You come here for the legendary casunzei: local half-moon ravioli filled with beetroot, ricotta, and poppy seeds. Drowned in butter, naturally.

Vallon di Tofana

rifugiodibona.it

FRANZ KRALER

Without Franz Kraler, Cortina would lack its sartorial edge. Here you find top-tier Italian and international luxury brands in spaces that are completely redesigned every season. It is exclusive, certainly, but the welcome is warm and the multilingual staff impeccably helpful.

Corso Italia 107 (and other locations)

franzkraler.com

CAFFÉ ROYAL

The obligatory stop for a final cappuccino before hitting the slopes. Drunk al banco—standing at the counter—just as it should be.

Piazza Silvestro Franceschi 12