Living Well, Unnoticed

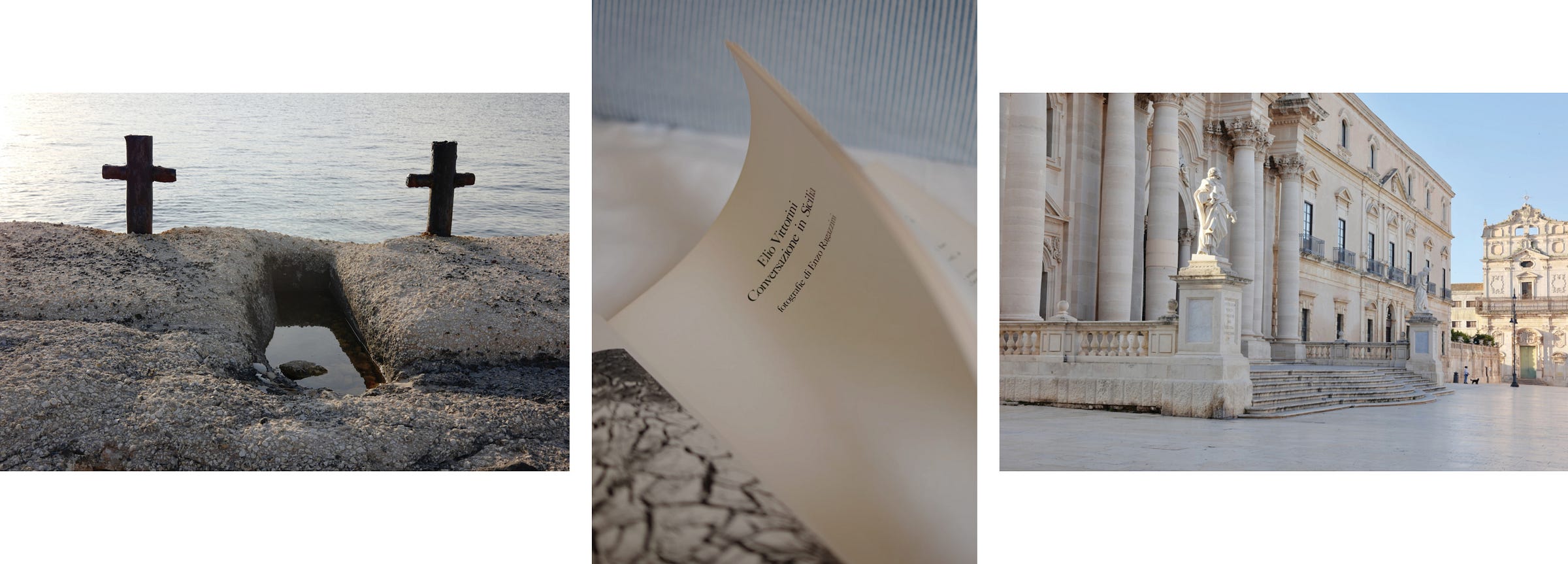

Ortigia's Lessons in Chaos and Discretion, Silverware and Caponata

If you’re Flemish, languages cling to you like fleas on a dog. Blame the genetics of being ruled by half of Europe since Julius Caesar marched over us in tortoise formation. At least he had the decency to call us the bravest. Since then we've learned to be pragmatic about nearshoring governance. Or was it just opportunism: natural-born pleasers?

My Italian, though, is still a conflict zone. Any Italian who cares for their language needs paracetamol after five minutes with me. I never studied it properly; a chunk comes from six years of Latin in school, another from decades of holidays and work trips. In Italy as in Spain.

I don't speak Italian; I speak Italiol, a language that's painfully brutta.

And absolutely hopeless when it comes to negotiating with the manager of a parcheggio in Siracusa.

I adore Italian parking garages, especially the old ones. The kind where you drive in, leave your keys in the ignition, and walk away, trusting a wiry 75-year-old in half-moon reading glasses sizing you up with a practiced glance. He'll wedge your car in a space designed for a cinquecento. Unscratched.

Our car doesn't allow for lots of luggage. Its boot fits exactly one and a half Ikea bags, two pairs of loafers, a small bag of Mr. Watson’s kibble, and a bottle of wine. More than enough, if it weren't for my wife's compelling desire to bring half of our silver cutlery collection, starched linen tablecloths and napkins, and at least four champagne glasses. Coupes, not flutes. The bare essentials for traveling in style. Which left the makeshift rear seats piled to the roof with a jumble of carrying bags in every shape and fabric.

Showtime for the parcheggio manager. A performer about to screw you over. With a smile. And me? I got my hackles up. Which blocked my Italian vocabulary. Spanish too. My brain—stripped of grammar and politeness alike—gave up. Assertively backed by my wife's rationale, it instructed me to unload the car and create a colorful tapestry of bags, enough to provision a small refugee camp, at the luggage depot next door. Also run, of course, by the parcheggio guy.

Miracolosamente.

Equally miraculous, the mood lifted as soon as our luggage pile was abandoned in the empty storage room. Linda was at the front door with Swiss precision, at five o’clock sharp. The last market stalls were taken down with the enthusiasm of a dentist's appointment, while a few American tourists, already eager for their 6 pm dinner, sipped their Day-Glo Aperol spritzes on the corner terrace, commenting on the peeling paint of the 18th-century baroque palazzi, one of which would be our home for the next few days.

Italians are discreet. Ovid said it over two thousand years ago: bene vixit qui bene latuit—he who lived unnoticed, lived well. It hasn't changed. It's what's behind the facade, away from the empty crates that still litter the market, that's of significance. It's what we found the moment Linda opened the door to the apartment.

Living in the heart of the market, it's only normal that you make the kitchen the center of your house. At Casa Sabir, dining is taken seriously, with a walk-in wine cellar carrying a selection of Sicilian wines, most of them natural, chosen with care. It's an artist's home, not renovated, but restored with the eye of an aesthete. Luca, the owner, kept what mattered: the height of the ceilings, the original colorful tiles, and the faded frescoes and friezes that must have appeared from under layers of paint and wallpaper. Signs of a life once lived differently, more elegantly than now.

It's the details that make this house stand out. You discover them by accident. You smile and think, "Shit, he even thought of that." Putting ventilation holes in the cupboard doors that match the flower motif on the tiles. Stencilled relief patterns in the shower wall. A patch of wall in lime plaster, tinted a pale blue just to match one of his artworks. It's renovation with passion. The work of someone who lives art.

And if the pastel-colored apartment is as restrained and elegant as Ortigia itself, the market underneath its terraces, with blue and red canopies—some faded, some vibrant—is its cheerful offset, fresh as a bouquet that is pressed unexpectedly under your nose. It's there when you wake up. Vendors debating meloni. That's politics, not fruit. The smell of simmering caponata drifts up. Tuna ventresca, marbled with fat and cut with ruthless precision. Gamberoni Imperiale, as red as the lava from Mount Etna, piled high on melting ice.

Cooking is not a solitary activity at Casa Sabir. The market is cheering you on as you cover the artichokes, stems up, with baking paper over medium heat. As you rinse the salt off the capers from Pantelleria. As you open a bottle of Alberelli di Giodo Carricante. You are cooking with the city, not in it.

And you know your wife was right (as usual) to bring the linen tablecloth and the silver cutlery.

You live well at Casa Sabir.

And quite unnoticed.

https://www.aestheticnomads.com/

Contributors:

Hans Pauwels, words - Reinhilde Gielen, photographs

Locations:

Casa Sabir, Ortigia, Italy