Old Enough to Know Better. Driving Anyway.

Crossing Europe in a Car Half Our Age. Part I: Athens to Abruzzo.

Maria hugs like a sunny Athens afternoon in autumn with a warmth I’d like to last. I melt into her arms. Her mezzo rolls out a melodious all-vowel welcome that lands in cutting consonants. Greek: a language that matches the land itself, all waves and rocks.

George is the steadiness to Maria’s fluidity. The confidence of a race car driver, a handshake firm and convincing. Driver’s eyes that assess me like a ninety-degree left-hander, committing to a line, certain in what’s coming. There’s not a spot of oil on the pearl-lacquered floor. The garage breathes high-octane fuel and strong Greek espresso, the cup Maria pressed into my hand. A rebuilt Meissen Blue G-model sits beside a Speed Yellow 964 awaiting bodywork. A Porsche timeline fills the wall behind them like a text balloon in a comic book. Mechanics work silently, tools speaking for them.

We could have gone to Germany to restore our car. A corporate job by IG Metall-unionized mechanics. With a mustachioed manager from Sindelfingen who gives no hugs. There’d be neither big-city chaos nor Athens Riviera laid-back elegance. There’d be weak coffee and less passion than efficiency.

Luke—a young meat trader who made his first money by cleverly double dipping in the farmer support and subsidy schemes of both the European Union and the United Kingdom—is responsible for my passion for cars. I must have been nine years old, spending every free moment devouring books slumped in the lounge area of the 1960s kitchen with its large bay windows and colorful dividers. He wore a suit and tie. A crisp white butcher frock draped over his left arm, and his right hand loosely on the roof of his silver BMW 2002 as he was talking to my father. He roared off, tires crying out, leaving two parallel rubber trails on the concrete.

I was hooked. On cars, business, and elegant attire. The latter two took nearly two decades to manifest. But even then, I knew that later I would drive a sports car: a Porsche 911.

The first was a 1985 Moss Green G-model Carrera 3.2 I bought in 1992. I was 32 years old, and I used it as my everyday car. Some say it gave the wrong impression for business. I never cared. When I pushed it to 190 km/h, the front became light as a feather. Beyond that, it felt like a countdown to takeoff. Sometimes it frightened the shit out of me. I was young and reckless; it didn’t stop me from driving fast.

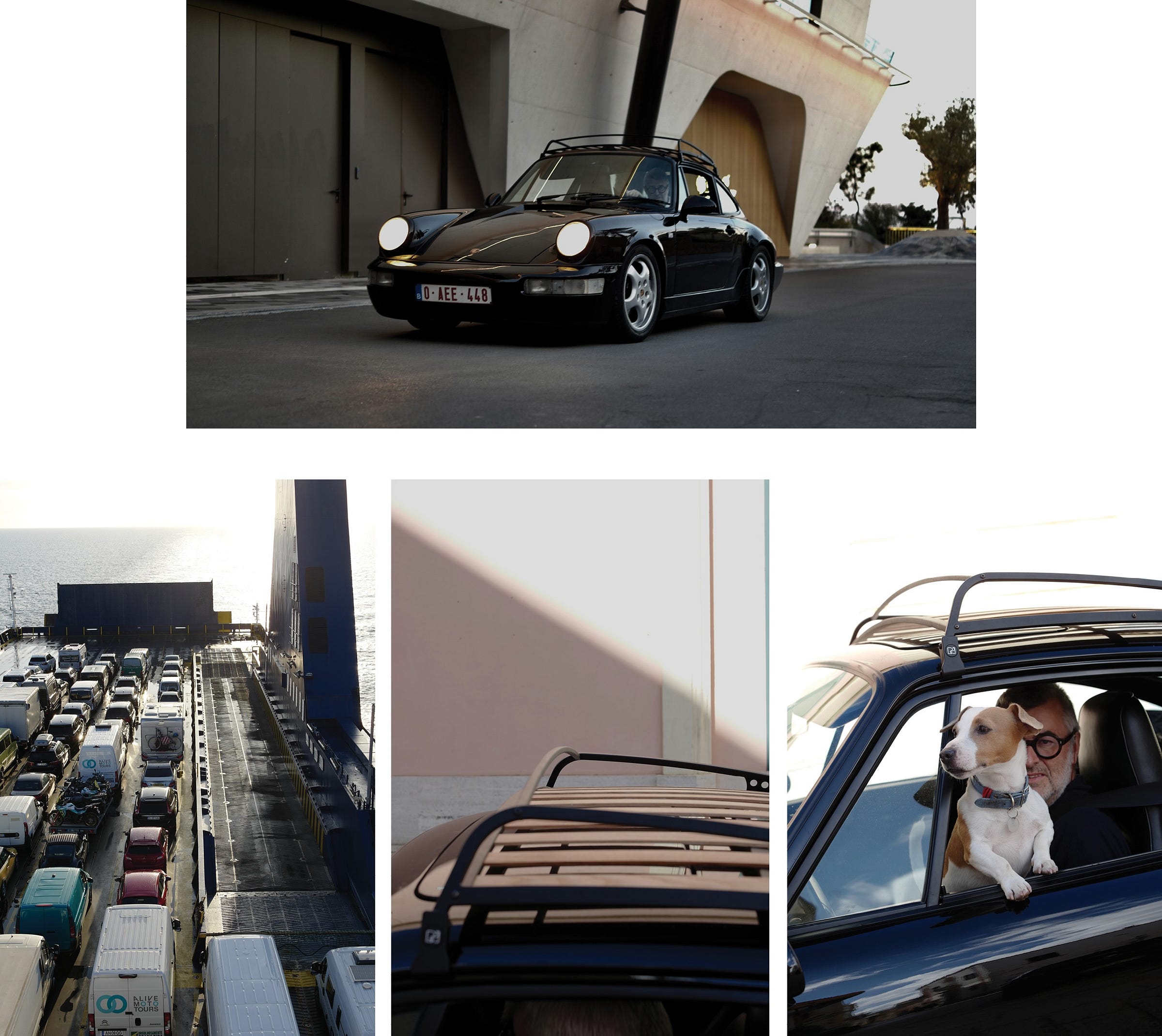

I traded it for a low-mileage all-black 964 in 1995. Porsche had accumulated massive losses in the early 1990s, spending heaps on the development of the 959 supercar and straightening out its production inefficiencies. There was talk of bankruptcy. But the 964 was a hit. Despite the German engineers’ mulling over how they could best confuse the drivers by hiding yet another rocker switch under the dash.

When it was launched, the 964 was a modern sports car that seemed glued to the road. Until one day the back snapped out brutally when I wasn’t expecting it. A full 360 on the wet Brussels cobblestones in front of the Royal Palace with both kids in the back on their way to school. I still hear the youngest—even today the most outspoken of the two—comment, “Il est taré, ce mec.”

Our parental guidance apparently never really stuck to HJ. Ce mec was me.

I love this car and never sold it. I smile whenever I’m behind the wheel. Which was very rare over the last twenty years or so. It was mainly parked at the house of a friend of mine, an absolute Porsche fanatic, in plain view from his living room until I had it trucked to Athens for restoration.

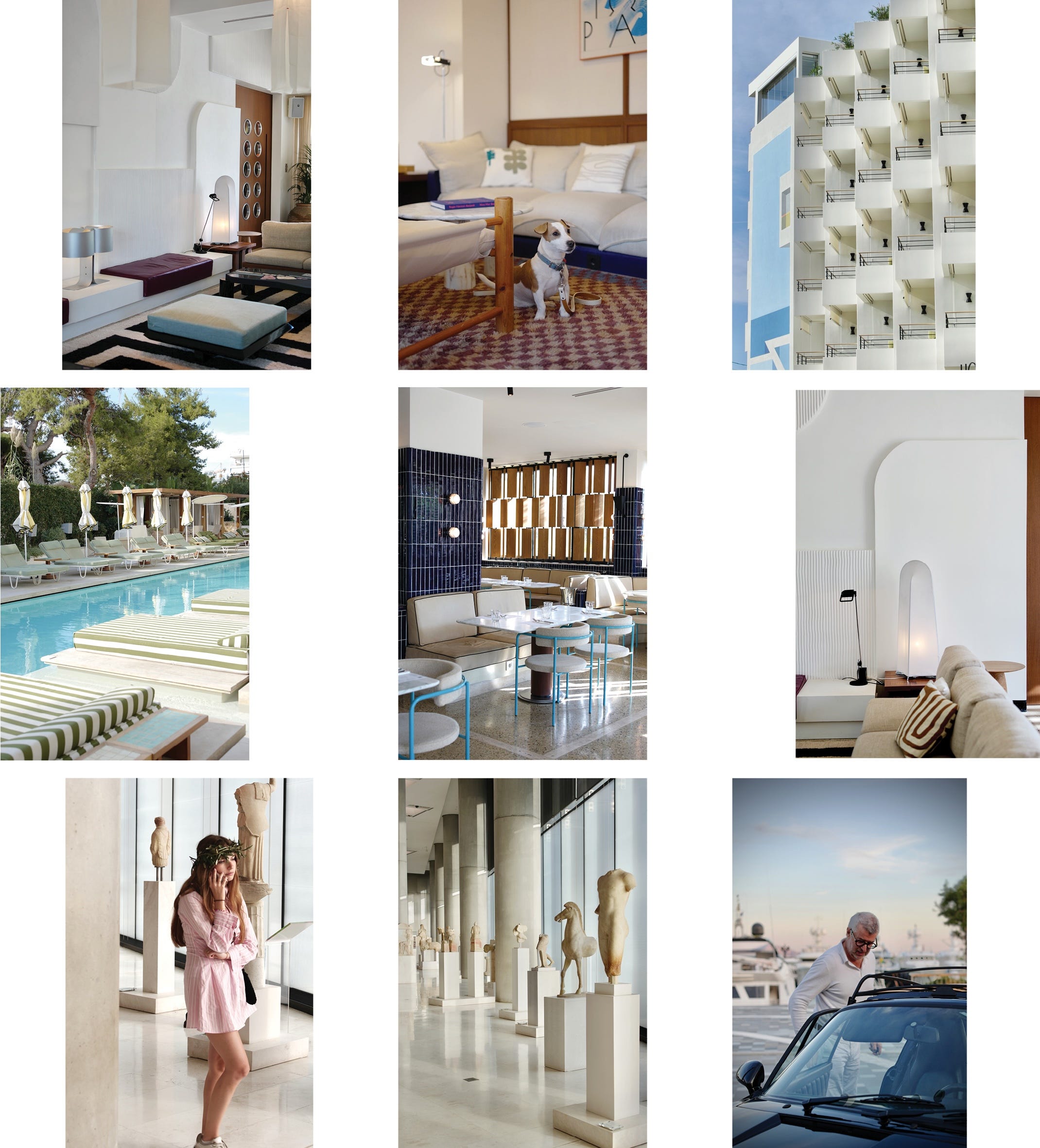

We picked it up eight months later. The day before, we dropped off a set of four new winter tires that we checked in as luggage on our flight. Traveling with a full set of tires, packed in Moroccan polypropylene zipper bags with a tartan design in distinctive Christmas colors, felt like an exotic last-minute solution for tire sizes nobody feels the need to sell in Greece. What should have been our first exciting drive with the now properly shod car ended after thirty minutes with a smell of burnt oil, an engine that needed to be taken out and fixed, and the hardship of having to spend five more gorgeous autumn days along the Athens Riviera in Glyfada and in the pine resin hills of Kifissia.

Elegant suburbs where the chaos of the city center made way for a gentler, more sophisticated Mediterranean life while the mechanics down the road put the engine together again.

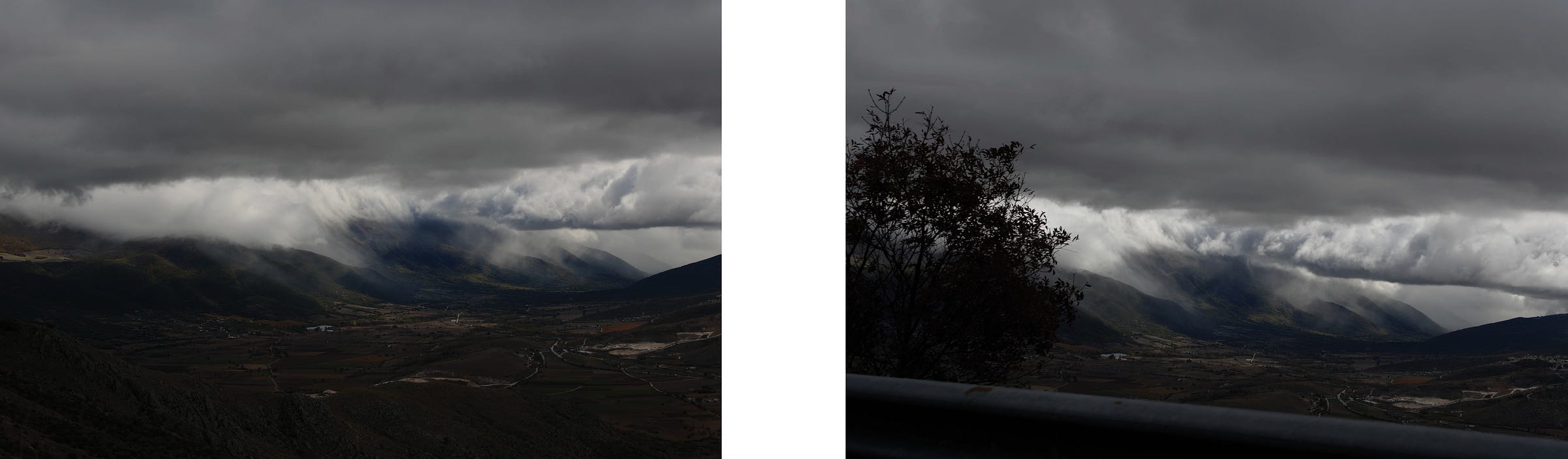

The leisurely five-hour hop to the Brindisi-bound ferry in Igoumenitsa became a hard run on pitch-black tarmac through Greece’s northern pines—no traffic, no margin, and a car we hadn’t properly test-driven since its rebuild. An act of faith in Greek wrenching, measured in shallow breaths that matched Epirus’s dark emptiness. Every sense up: we chased down each shudder, counted every tappet’s clack, and watched the oil-temp needle creep, ready to pull over into nothingness and surrender to the disposition of a random passerby with a decent grasp of English.

Then the floodlit port took the fear out of it: a diminutive 911 slotted among triple-axled Albanian artics, stretched Romanian vans, and oversized SUVs, waiting for stevedores with traffic wands in fluorescent windbreakers. Diesel hung heavy under sodium; generators thumped; a death rattle whined from a winch on bad bearings. We took our place on the greasy, ribbed deck, toeing past scuffed steel and bare anchor points while lashing chains clacked to life on a lower deck. By morning we were all the same—drivers, truckers, tourists—blinking into new air as gulls screeched us down the stern ramp in single file.

The Salento has every right to its article. Puglia per eccellenza. The easygoing peninsula deserves more than a hit-and-run lunch and a November sun soak. We backed out of an Ionian dip the moment some surfers showed up in wetsuits. Bravery postponed.

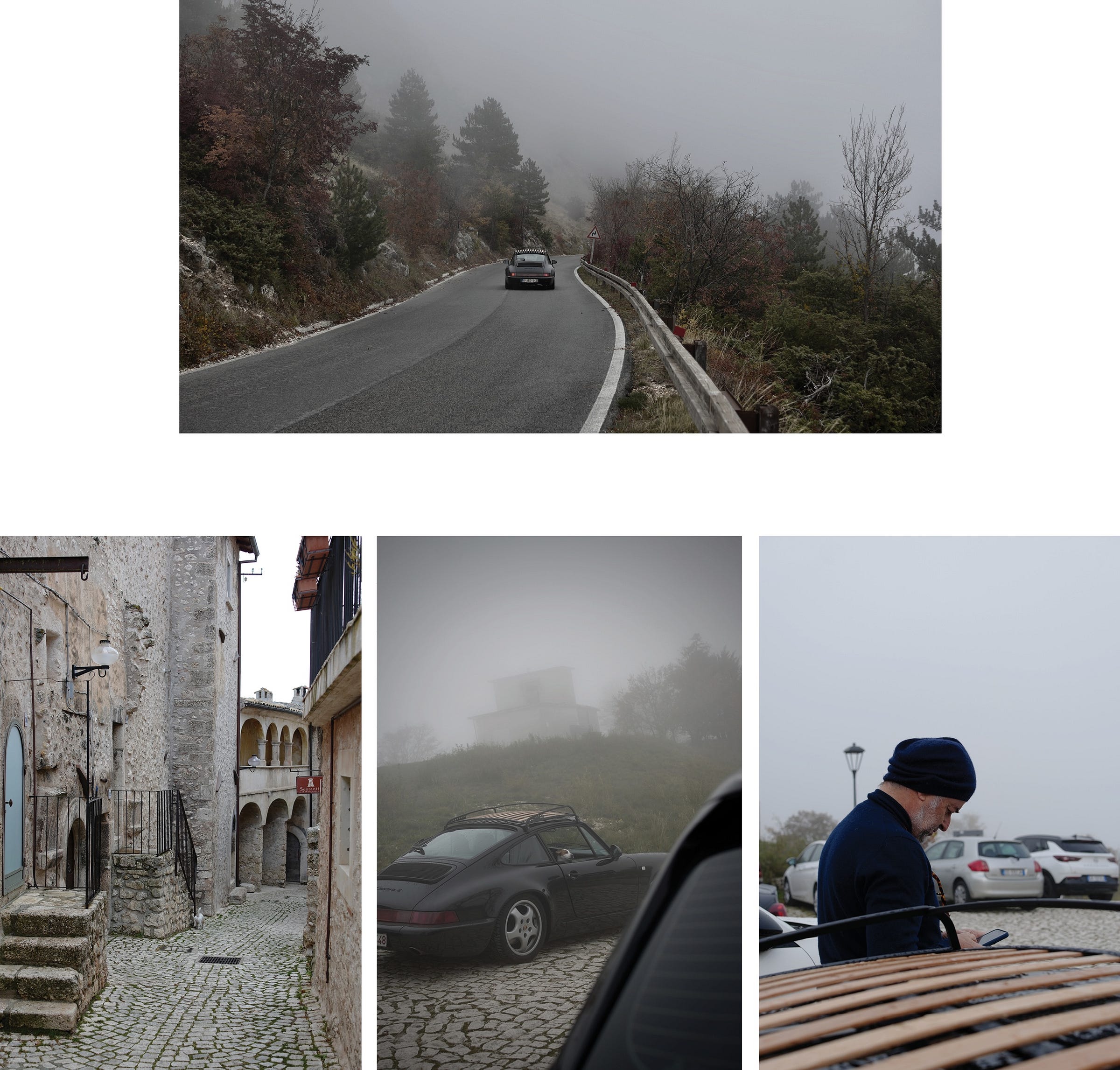

Abruzzo was a pin on the map between Salento and Venice. The E55 along the Adriatic was dead-straight tedium: speed-camera gantries, lane closures, and phantom roadworks. Night had settled by the time we turned into the Aterno Valley, unsure if the black mass to the north was cloud or mountain. Up SS153 the answer arrived: my idiot grin; second gear singing in tune; weight loading before every turn-in. SP98 to Santo Stefano di Sessanio was hairpin after hairpin, the rear squatting as I fed the throttle through each apex.

I only had one more wish: a light dusting of snow to test the Hankook winter tires.

And maybe also a good meal.

Santo Stefano is stones, fog, and warmth. Stones marked by hands—roughly hewn, slowly worn, carefully restored. Reflections on wet limestone; wood smoke in the alleys; traces of ordinary lives, hardship, festivities, abandonment, and regeneration. We found the reception near the village square and recognized the warmth of mountain villages: unquestioned generosity behind few words and spare gestures. We felt folded into the village, temporarily locals living the mountain’s simpler rhythm. Contributors, not exploiters.

But it is through its recipes that you really get to know a region. And that’s where Sextantio Albergo Diffuso excels. Dino Como, for ten years the right hand of Niko Romito at the three-Michelin-star restaurant Reale, lets the land speak through its ingredients at Sextantio Cucina, the hotel restaurant. Lentils with pork rind and bay leaves; black cabbage, apple, and horseradish; and orange, capers, and tarragon were among the finest courses we’ve had in Italy. Researchers from the Museo delle Genti d’Abruzzo collected popular local recipes passed down by word of mouth. Dino turned them into quiet, precise plates that feel and taste both traditional and contemporary. This is not cucina povera; it is the self-sufficient cuisine that applies rigor and sensitivity to local ingredients within a natural calendar.

Food true to season and place enjoyed in a centuries-old wool dyeing building at candlelit wooden tables with cane-seated chairs. In a brochure it might have looked fake. Here it was a perfect fit.

There was frost when we left for Venice. The Hankooks did their job in the cold.

We got lost on a roundabout near L’Aquila—only in Italy. A battered BMW 2002 took it with flair. The aging driver’s flat cap looked as seasoned as his car.

As I drove onto the motorway, I wondered if Luke was still alive and if he’d still be in meat without the double dipping.

https://www.aestheticnomads.com/

Contributors:

Hans Pauwels, words - Reinhilde Gielen, photographs

Locations:

PetroRetro 911 specialized Porsche workshop, Athens, Greece

The Twentyone hotel, Kifissia, Athens, Greece

Papaioannou restaurant, Kifissia, Athens, Greece

Luisa World, Kifissia, Athens, Greece

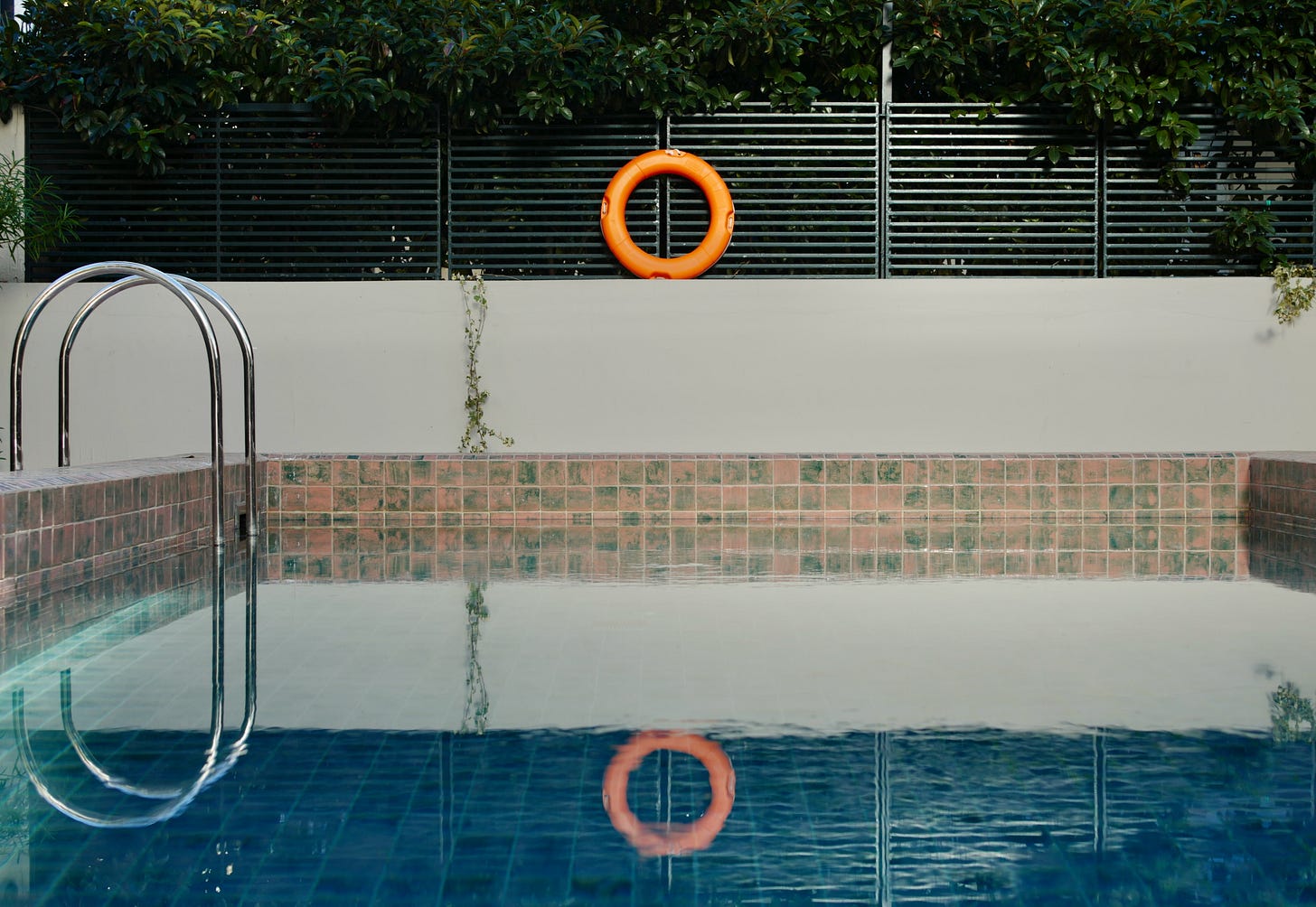

Ace Hotel & Swim Club, Athens, Greece

The Acropolis Museum, Athens, Greece

Astir Marina Vouliagmeni, Greece

Santo Stefano di Sessanio, L’Aquila, Abruzzo, Italy

Sextantio Albergo Diffuso, Santo Stefano di Sessiano, L’Aquila, Italy

L’Aquila, Abruzzo, Italy

Stunning photography, exquisite storytelling. The car - even (particularly?) to a no-car two-wheel explorer - looks beautiful and the drive memorable. You pick the very finest stopping off points!

My very first one was a black 964 and i'll never forget it!