Over Coffee, A Horse

From Rothenberg in New York to Bräunerhof in Vienna—Art as Compass, Café as Refuge

I guess it must have been the early nineties, when New York was still rough. Anything above 97th Street felt dodgy. Not that we went there; we were recommended to avoid it. There were carcasses hanging on rails dripping blood and fat on Chelsea pavements. Of course we went there. Now we don't. And SoHo was filled with artist studios and galleries rather than luxury brands. But we still go there.

And there was something new: coffee.

Not the drip coffee made hours ago and still sitting on a hotplate, tasting like the worn-out Goodyears on the builder's two-tone Ford Bronco. But the real espresso, brewed on a La Marzocco in steel-columned lofts with soaring stuccoed ceilings. Served from marble-top counters. Coffee that tasted like Italy. Sipped among dazzling patrons in bars that oozed Reagan's new-money optimism.

Jonathan Morr Espresso Bar on Greene Street was our coffee hangout.

Every morning, after swimming, I still drink a large, French-pressed coffee from a mug we bought there. Its logo—designed like a Sator Square and still brutally contemporary—stares me boldly in the face. It's not their cappuccinos that I remember. Nor the overheard conversations of downtown artists talking about video art and the World Wide Web.

It's a horse.

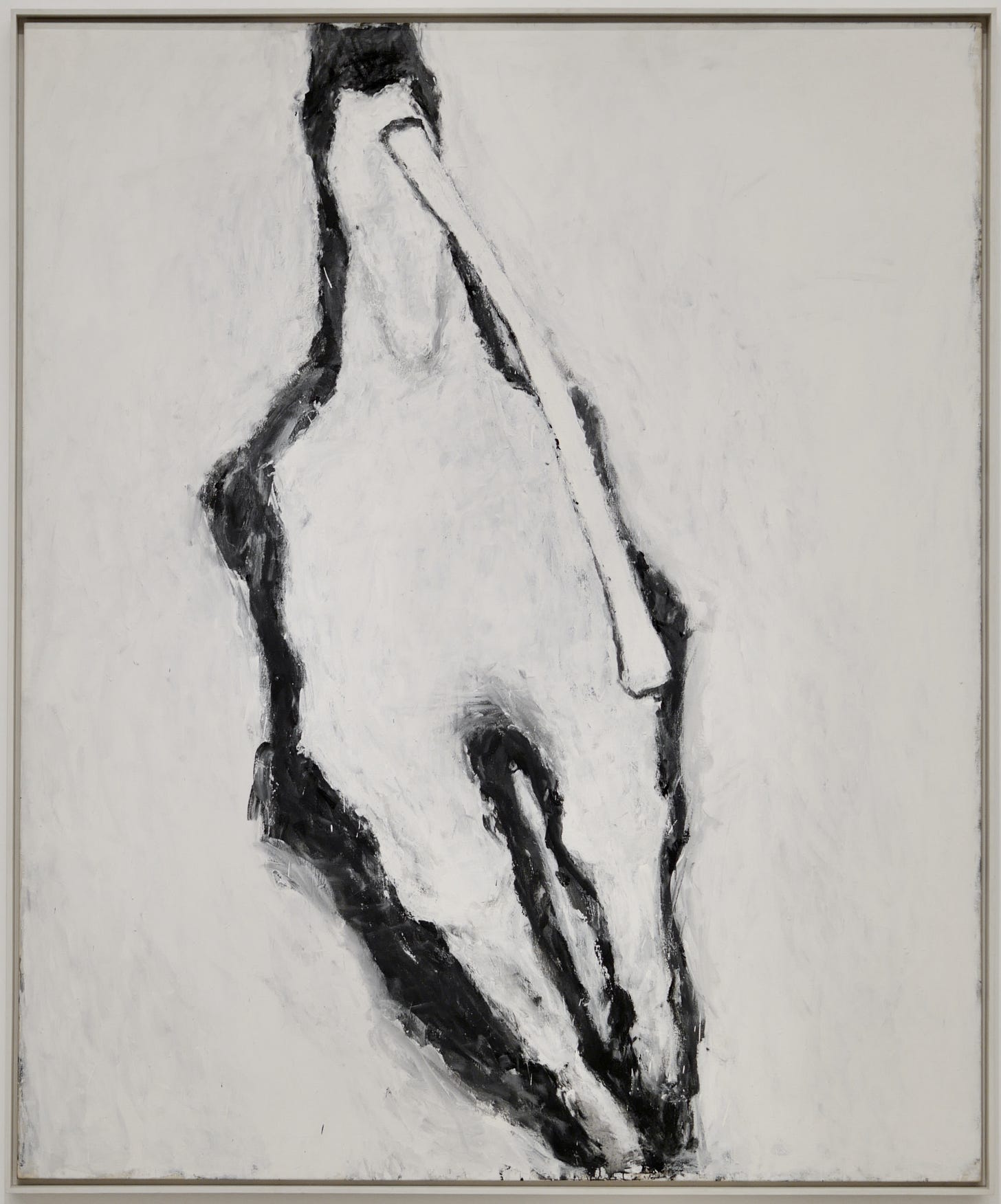

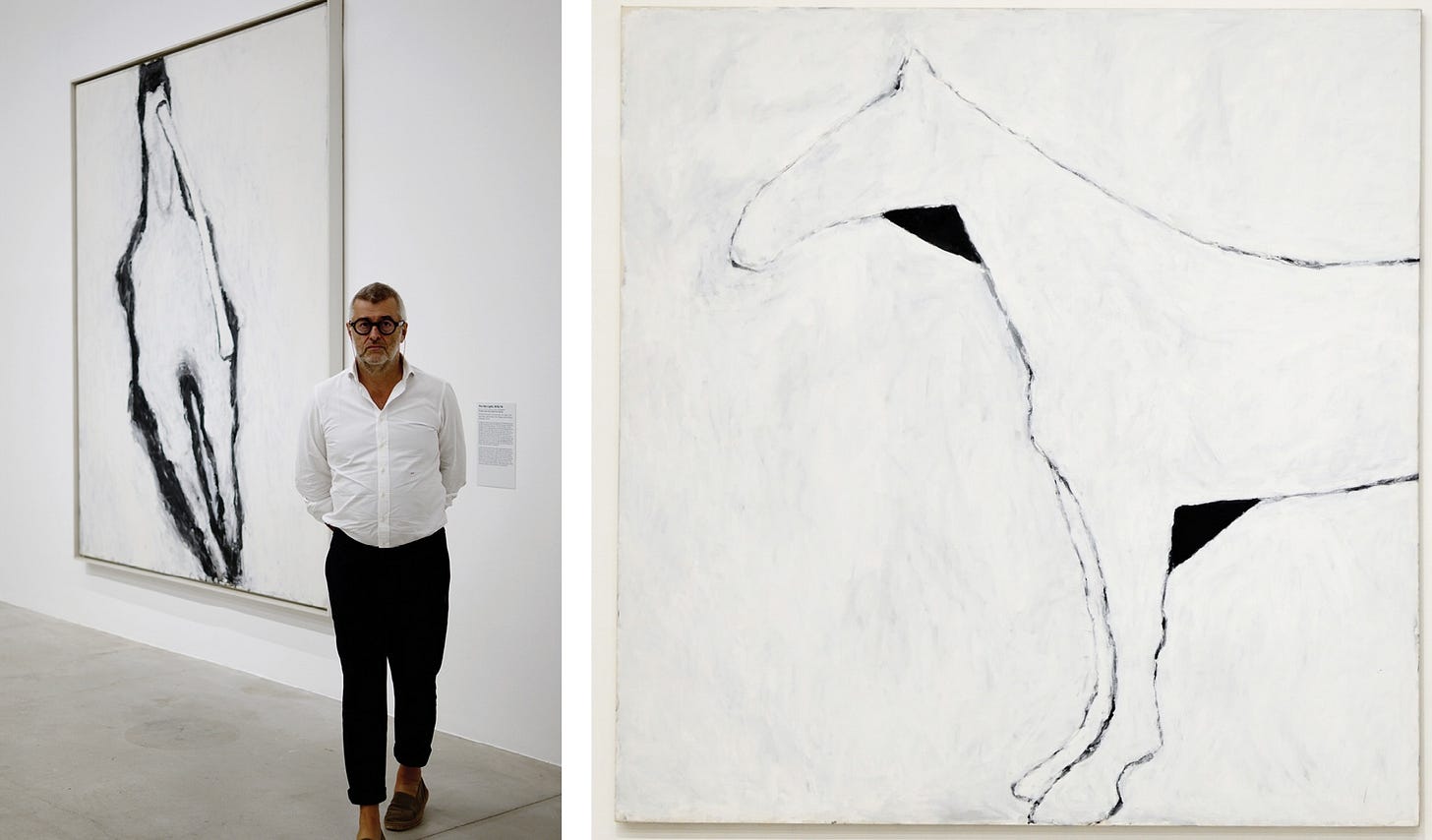

Or rather, Susan Rothenberg's oversized painting of it. Black contours brushed over thick layers of matte white acrylic paint. Overpowering the entire space from the back wall, mingling with the smell of ground beans. There's something about Rothenberg's horse paintings. They are strangely abstract, devoid of emotion, yet full of life, movement, and feeling. Frozen in motion like Muybridge's photos. Framed by geometric outlines like Bacon's triptychs.

Painterly horses. Archetypes of poise.

Rothenberg isn't well-known in Europe. There is some early work of hers at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and the Tate Modern in London. So when we found out that there was a retrospective at the Kunsthalle in Krems an der Donau, we didn't hesitate. Visiting Vienna would be our excuse to see her work again.

It wasn't our first encounter with Vienna. I remember roaring along the German motorway at 180 kilometers per hour in a Golf GTI, heading for Vienna in the early 80s. There was the Spanish Riding School with its Lipizzaner stallions and my favorite smell of all: a horse's sweat on waxed leather. Don't judge me by my eccentric tastes. There was Hofburg baking in the summer sun. The city felt overwhelming and languid.

I also remember staying at the Sacher hotel for a single night somewhere in the 90s with a business meeting the next day. It felt stuffy and boring. Around 2010, I met with Do & Co, Austria's main catering company. I was trying to sell them chocolates. It felt like selling sand to the Sahara. I've never shied away from impossible challenges.

It's fair to say that Vienna hasn't been a town on our radar until Rothenberg's horses called us back.

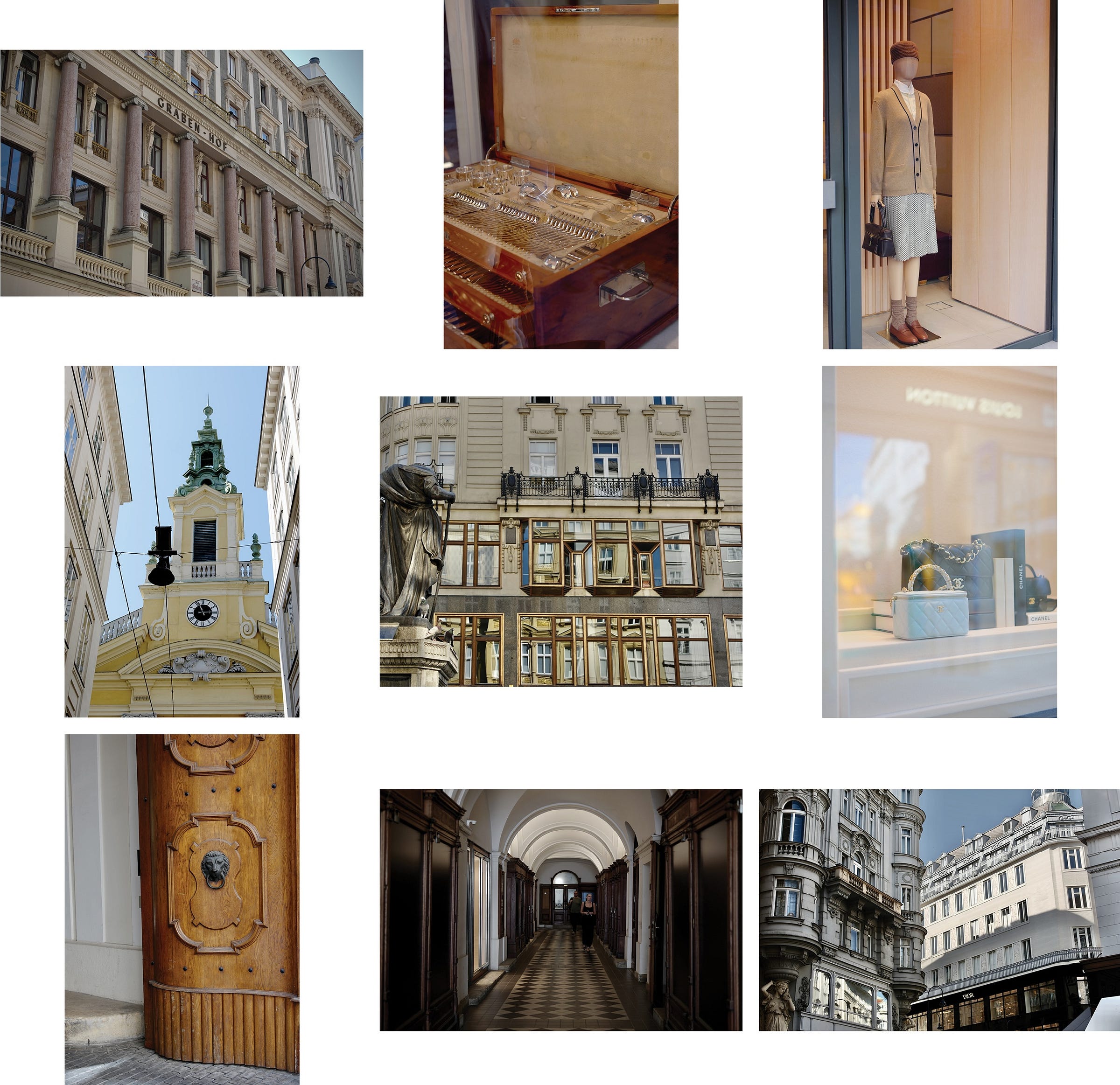

The city's still overwhelming. It's splendidly imperial, built on generations of ecclesiastical and aristocratic wealth. It exudes power through grandeur: an oversized city in a diminutive country, like an older man in a suit, tailor-made for his more vigorous and bulkier days. I've seen a few around, one with skinny legs in a 2500-euro pair of lederhosen and a loden janker.

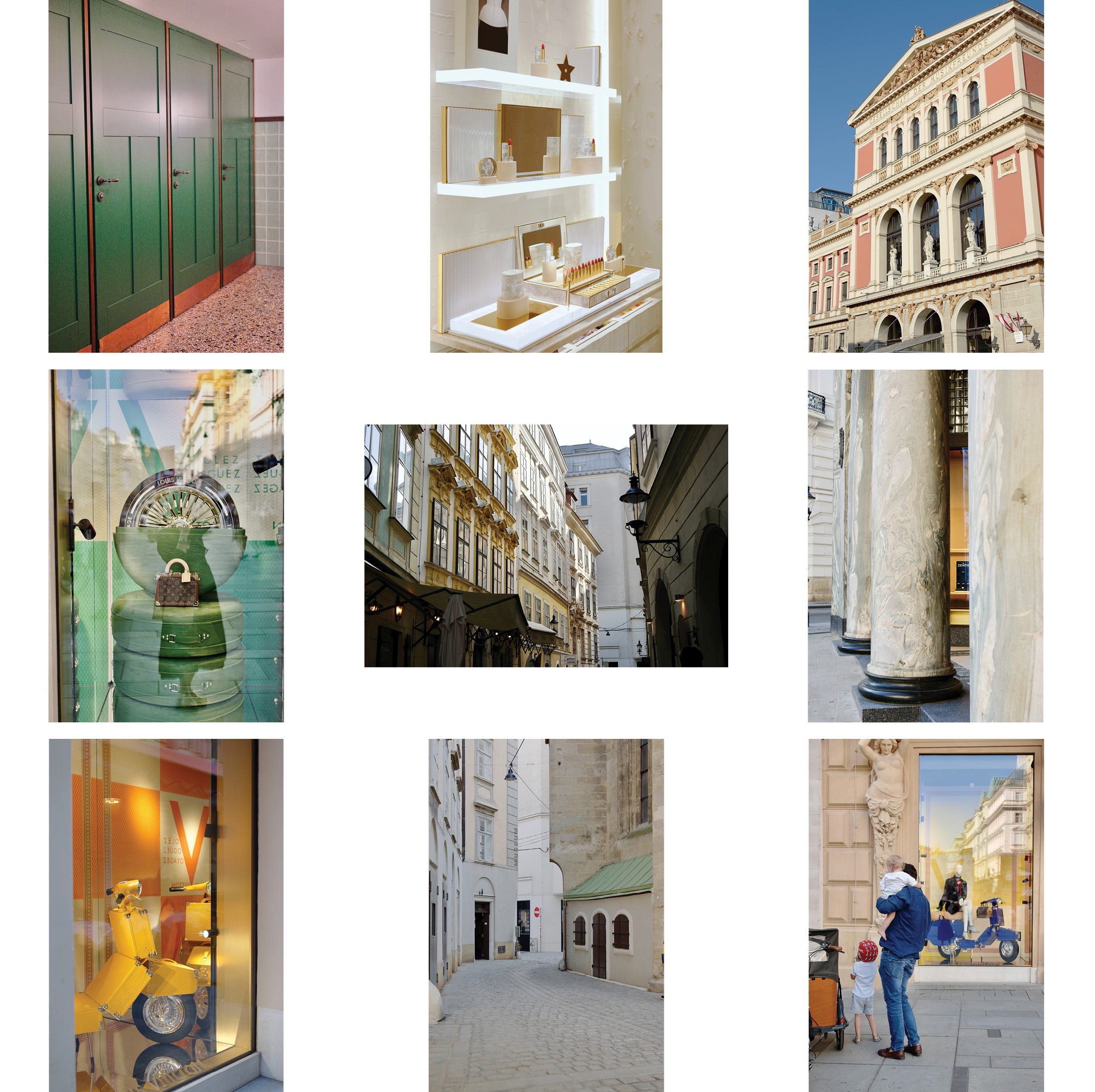

It's no longer languid. It's full of tourists. Asian group tours, bussed in for the day. Passengers from Danube cruise ships, marching through the same rounds, seeing the same sights, sipping a melange in cafés that once had a soul. We walked in and out of landmark cafés that looked like sterile film sets past counters filled with overpriced pastries produced by the same industrial bakery company. With waiters that still looked the part but lost the vibe, even when addressed in fluent German.

But you can still get lost in the city's alleyways and come across some truly quaint authenticity. The shop—recognizable only because the front door was open—where a young couple was tailoring lederhosen. A 90-year-old unlit cocktail bar with a list of unacceptable activities that was longer than its menu. An antique silver dealer with a 240-piece Art Nouveau cutlery set, priced at 48,000 euro. Two women running a store that only sells men's underwear, socks, and ties because a man's cachet truly shows once he undresses.

And Café Bräunerhof, the one that lured us in because it felt like how a café should be: cozy, lived-in, and just shabby enough to make it cool. With a Stammtisch and waiters that vet you as you walk in.

Because it's the guest who adjusts to the locale, not the other way around.

I suspect this goes for Vienna too. To really understand the city, act like a Wiener.

And keep your tie on when you undress. For cachet.

https://www.aestheticnomads.com/

Contributors:

Hans Pauwels, words - Reinhilde Gielen, photographs

Locations:

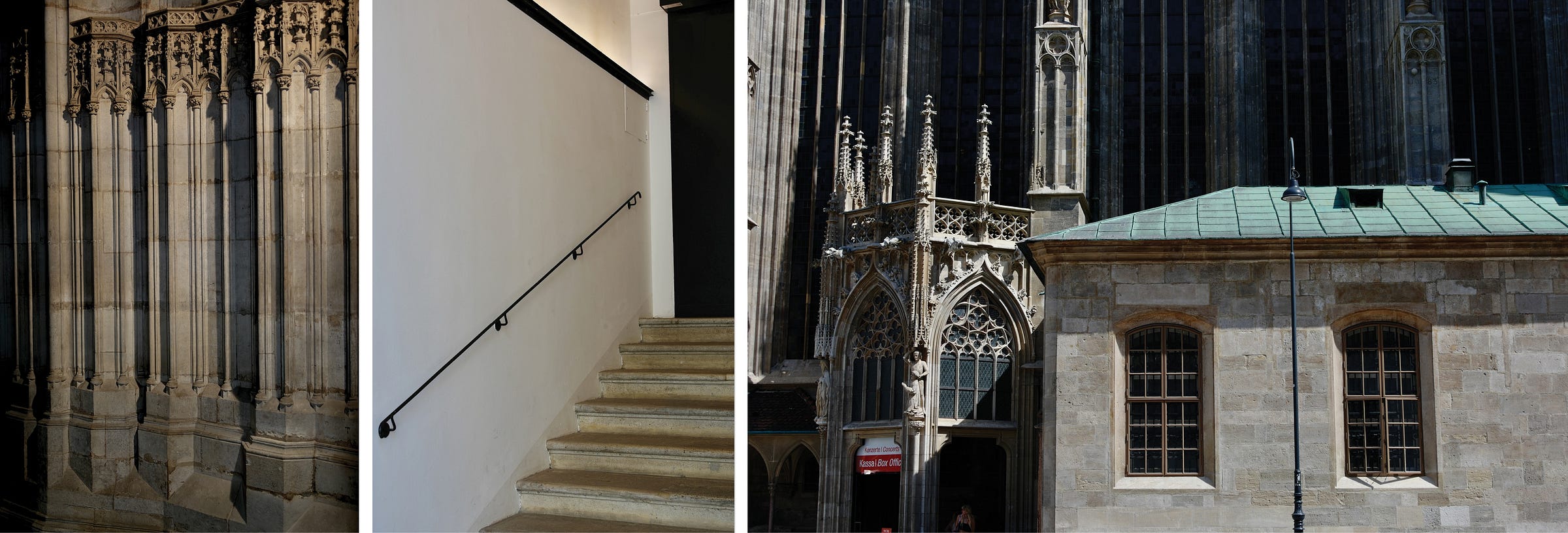

Kunsthalle Krems, Krems an der Donau, Austria

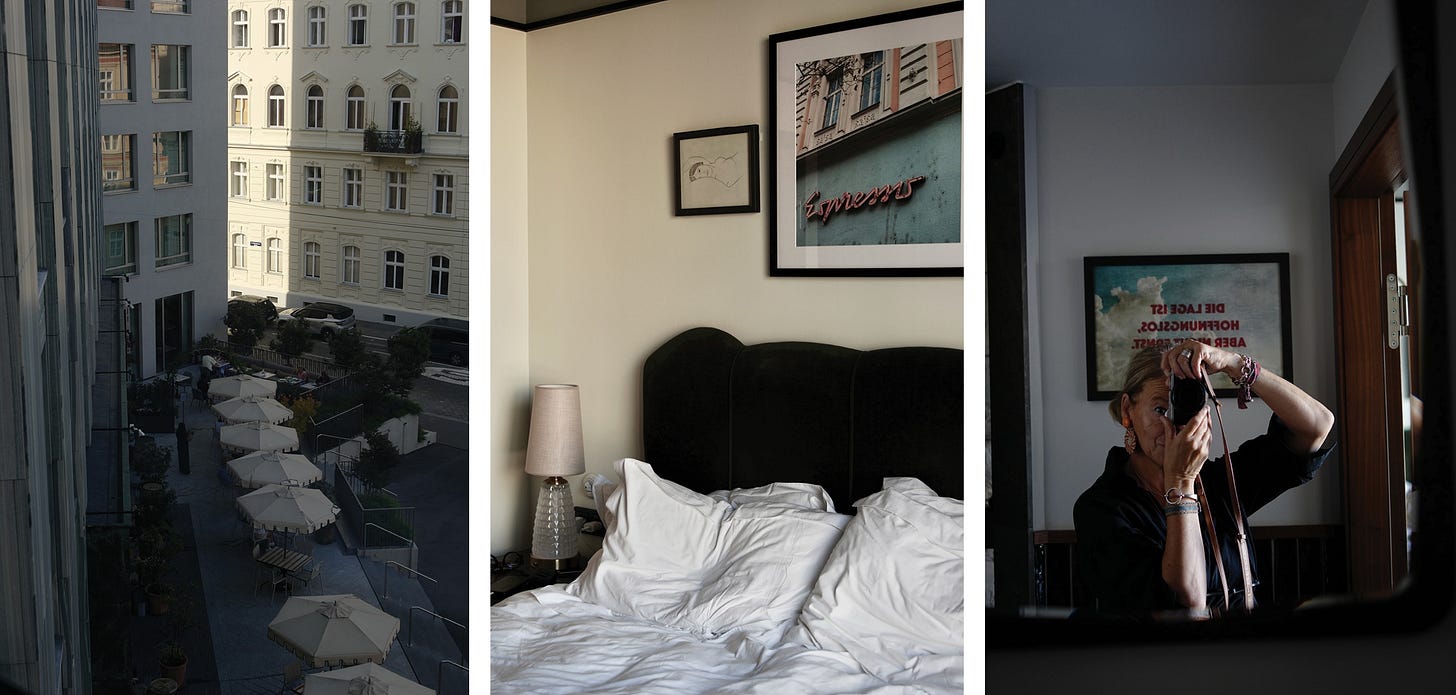

The Hoxton, Vienna, Austria

Bonbonnière, Vienna, Austria

Dior Boutique, Vienna, Austria

Bräunerhof Café, Vienna, Austria

Il Cavalluccio Restaurant, Vienna, Austria

Hotel Regina, Vienna, Austria

Fabio’s Restaurant, Vienna, Austria

Musikverein, Vienna, Austria

Landesgalerie Niederösterreich, Krems an der Donau, Austria

Artworks:

Susan Rothenberg, For the Light (1974), Whitney Museum of American Art

Susan Rothenberg, Algarve (1974), Hall Collection

Regula Dettwiler, Unvergesslich (2025)