Villaggio ENI - Cortina's Modernist Mountain Utopia

70 Years Ago, Industry Leaders Embraced a Social and Cultural Mission

Enrico Mattei had a knack for making enemies—powerful enemies.

It got him killed.

His rise from humble beginnings to one of Italy’s most influential post-war figures was meteoric and contentious. Mattei was a man of contradictions: a shrewd industrialist with utopian ideals, a corporate leader with an eye for the social good. As CEO of ENI, Italy’s national energy giant, he dragged his war-torn country into a new era of modernism, carving a place for it among global powers.

He wasn't known for subtlety: he broke the oligopoly of American oil companies, negotiated energy independence for Italy, and infamously meddled in geopolitics, from the Middle East to North Africa, supporting Algeria’s liberation from French colonial rule.

His enemies called him a rogue. His admirers, a visionary.

Mattei’s plane never landed at Linate Airport that October night in 1962. It disintegrated. Lowering the landing gear triggered a hidden bomb. It was a shadowy, cinematic end to a man whose ambitions had touched every corner of post-war Europe. Yet Mattei’s vision was not just industrial or geopolitical. It was cultural.

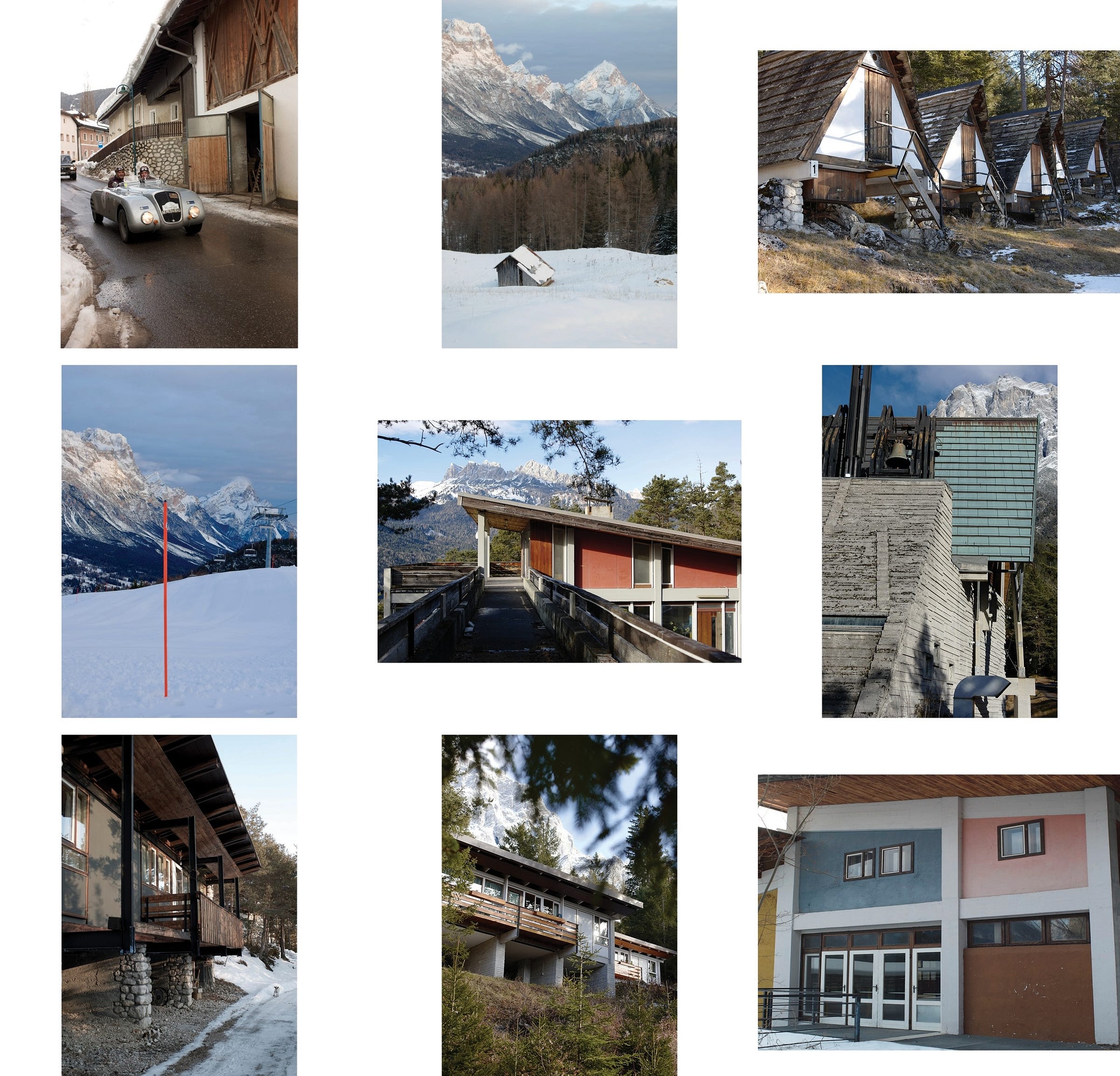

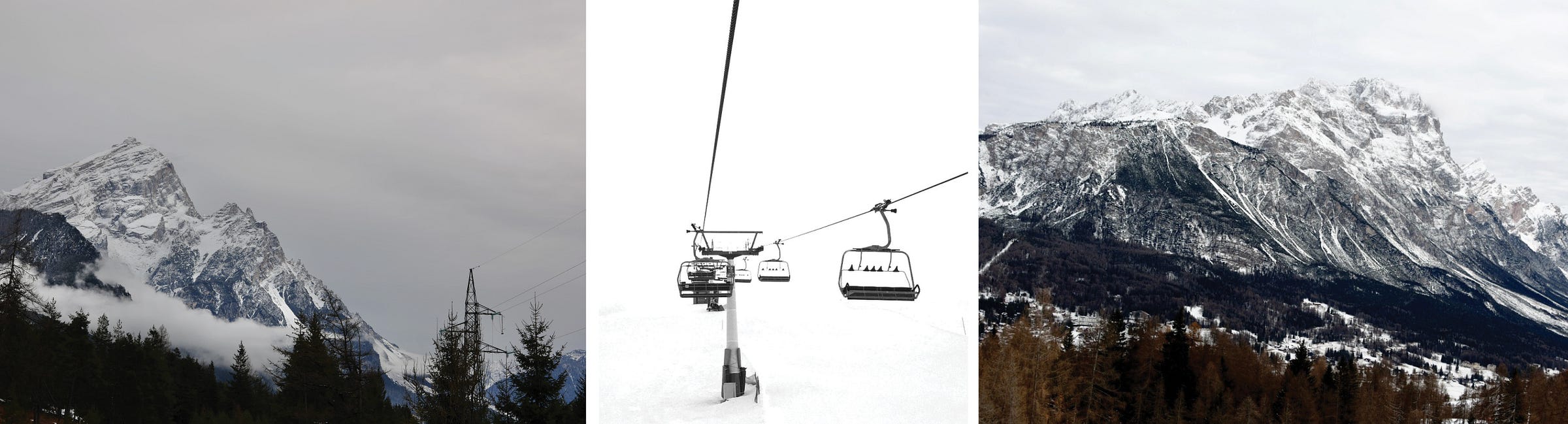

Nowhere does it survive more poignantly than in Villaggio ENI, a small modernist utopia nestled in the Dolomites near Cortina d'Ampezzo.

At Borca di Cadore, where Monte Pelmo rises pink and radiant in the morning sun, Mattei’s vision endures, subtle but unmistakable. His industrial empire was built on the labor of thousands, but he saw his workforce not as a divided hierarchy of executives and laborers but as a unified collective. In this vision, Villaggio ENI played a central role. Conceived as a company retreat, it was not a luxury reserved for managers but a shared space for all ranks.

Here, workers and executives spent their holidays side by side, staying in identical chalets, studios, or hotel rooms, equal in size and design. Traditional markers of social class were deliberately erased, and in their place was an egalitarian community where families would meet at the same bar, share pews at the same church, and enjoy a lifestyle shaped by the innovations of Italian modernity: Agip fuel, Vespa scooters, Fiat 500s, and the buoyant optimism of post-war rebirth.

To build this utopia, Mattei needed an architect who understood not only form but purpose.

Enter Edoardo Gellner.

A pioneer of modernism and architect of the Agip motel in Cortina, Gellner approached Villaggio ENI with the same comprehensive spirit as the Bauhaus architects, pioneers of functional and integrated design. His work here was a “total design” project, encompassing urban planning, architecture, interiors, and even the smallest details of furniture and fittings. He envisioned a community that would encourage spontaneity and interaction. The chalets, built in modular clusters across the landscape, created intimacy without isolation. Communal spaces—the bar, the church, the tabacchi—were carefully placed to serve as natural gathering points.

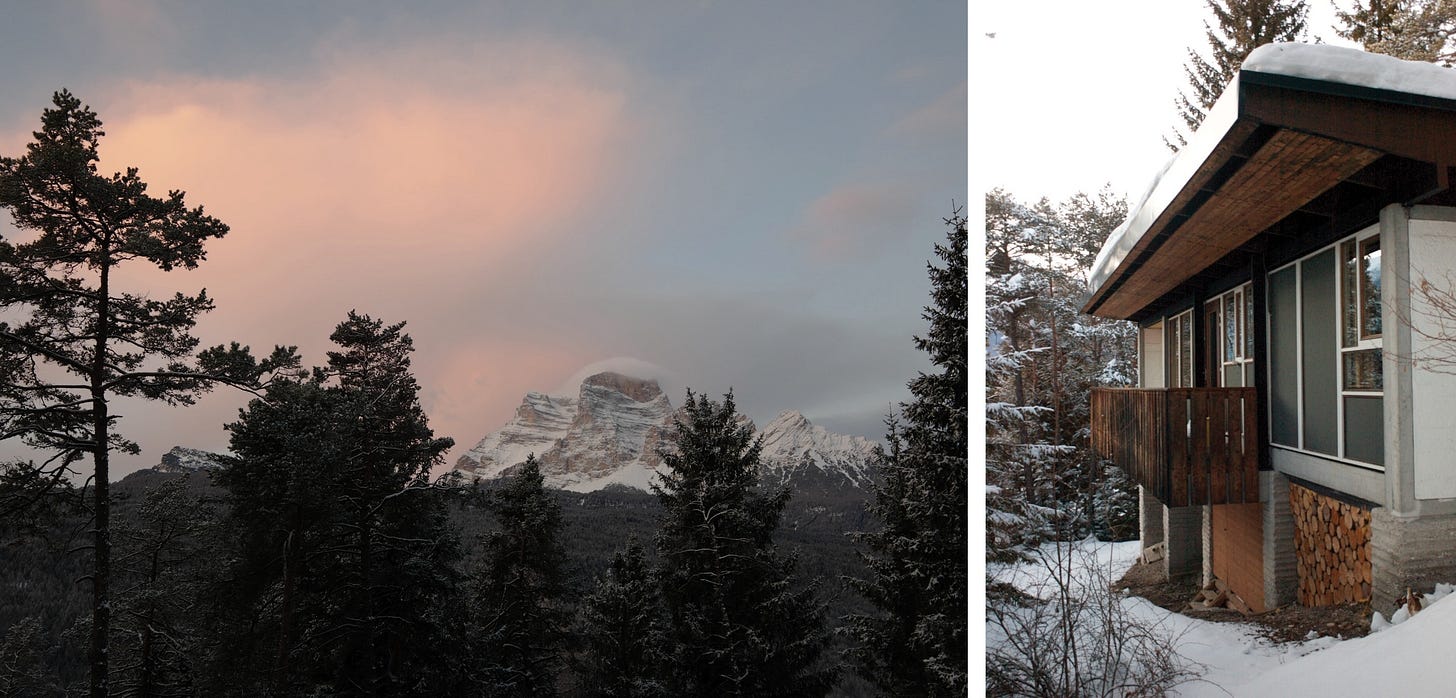

The chalets perch amid pine forests like angular sculptures. Through the south-facing windows of their minimalist frames, the Dolomite scenery bursts forward—raw, majestic, and intrusive. These were homes designed not to tame nature but to showcase it, as if to remind visitors of their humble place within its grandeur. Inside, the contrast is striking. Bright yellow concrete floors complement blue and red walls, vibrant Formica kitchen worktops, and furniture of disciplined simplicity. Gellner’s designs speak to a harmony of contrasts—the bold and the serene, the natural and the manmade.

Gellner’s architecture was radical for its time. It rejected the heavy, ornate traditions of Italian alpine design and replaced them with an unapologetic modernism: angular forms, sloping pent roofs, and minimalist interiors. His materials were local and honest—stone, timber, concrete—and his palette restrained, save for those daring pops of yellow, blue, and red. In 1956, when the first chalets were completed, the effect must have been disorienting—an alien landscape of geometric structures set against the jagged Dolomites. Yet, to those who stayed there, Villaggio ENI offered something visionary: a model for a new Italian way of life.

Villaggio ENI was more than a design triumph. It was a social experiment—a company town reimagined for the modern age.

But time has not been kind to this utopia.

Many chalets have been sold as holiday homes, their interiors gutted and replaced with Ikea furniture. The bold colors have faded, and windows now hide behind laced curtains. The bar and tabacchi, once the heartbeats of community life, have closed. Without its original purpose—to foster connection and equality—the architecture has become a quiet monument to an idea that failed to thrive.

Luckily, some villas have been bought by design enthusiasts and remain perfectly preserved.

The church still stands as the crowning jewel of Villaggio ENI. Gellner brought in Carlo Scarpa, his friend and mentor, for the design. Its stark yet commanding form rises from the mountainside like a solemn sentinel. Inside, light filters through narrow slits, illuminating bare concrete walls and wooden beams with a reverence that feels almost sacred. Religious services are infrequent, but the structure remains open for occasional events. Its presence is indelible—a reminder of what Villaggio ENI was meant to be and what it could never fully become.

Enrico Mattei dreamed of a future in which architecture could reshape society—a vision both noble and naïve. In Borca di Cadore, his legacy persists as both triumph and failure. Villaggio ENI remains a place of arresting beauty, where the echoes of a modernist utopia linger amid the pine trees in the foothills of the mighty Monte Antelao.

Design can shape spaces, but it cannot always shape people.

Another failed utopia, and yet, standing in a chalet kitchen, the pink morning light pouring through those expansive windows, one cannot help but marvel at the ambition—and the grace—of it all.

Reach out to us if you want to stay in one of the perfectly restored chalets. We’ll happily bring you in contact with the owners.

https://www.aestheticnomads.com/

Contributors:

Hans Pauwels, words - Reinhilde Gielen, photographs

Locations:

Villaggio ENI, Borca di Cadore, Italy

Chiesa del Nostra Signora del Cadore, Borca di Cadore, Italy

So interesting. Thank you for sharing!

This is such an amazing region to ski. For years we went to La Thuile. I had never heard this story in particular. The use of the primary colors do very striking, along with the clean geometry, an austerity that mid-century modern in the US was never quite able to accomplish.