All Woman and Half a Man

Fiore de Henriquez: Scars, Stone & (Ir)Responsible Parenting in Peralta, Tuscany

Our son is still mad at us about Peralta. Even after more than twenty years. Because we left him in an Italian hospital, just out of recovery from an emergency appendix operation, groggy, bewildered, and alone.

He was eleven.

We were starving. The trattoria down the road was irresistible.

Parenting doesn’t always look exemplary in hindsight. But that moment is how Peralta entered our family story. As irreversible as the scar on his side.

Peralta lies at the end of the road, literally. You drive inland from Forte dei Marmi toward Lucca, then turn off at Pieve. The road narrows, curling upward in switchbacks better suited to coughing Ape three-wheelers and battered Cinquecentos than to SUVs. At one bend, you squeeze through with centimeters to spare: a raised granite threshold on one side, a medieval wall on the other. The doorstep is on Google Maps: a light-gray triangle sticking out into the Via di Agliano Peralla.

Most people stop there.

Don’t. Another kilometer up, the road ends at the hamlet of Peralta, hidden among olive and lemon trees, smelling of citrus and resin. Accidental, like you’ve wandered into someone’s hideout.

It was nearly lost. Castruccio Castracani built a castello on the ridge in the 14th century; the foundations still brood above the hamlet. By the mid-20th century, the families who’d lived off olives, sheep, and chestnuts had left for lives with a future. Roofs collapsed, floors gave way, and brambles swallowed entire buildings. When the sculptor Fiore de Henriquez followed the goat paths up in 1967, only two houses were inhabited. She saw ruin and beauty.

We stayed there in the spring of 2004, a few months before she died. By then the buildings had long been restored by local craftsmen who hauled materials up by mule and celebrated each hard-won milestone with copious food and enough wine to make the walk home along the mountain paths a life-threatening affair.

She kept the medieval austerity but eventually conceded bougainvillea and jasmine. Herbs came first: rosemary, sage, and thyme. And lemons for the oil to slick across her ice-cold gin martinis, the fruit plucked minutes before serving. A pool was blasted into an olive terrace and winched up piece by piece: a blue cut of sky overlooking the Camaiore valley.

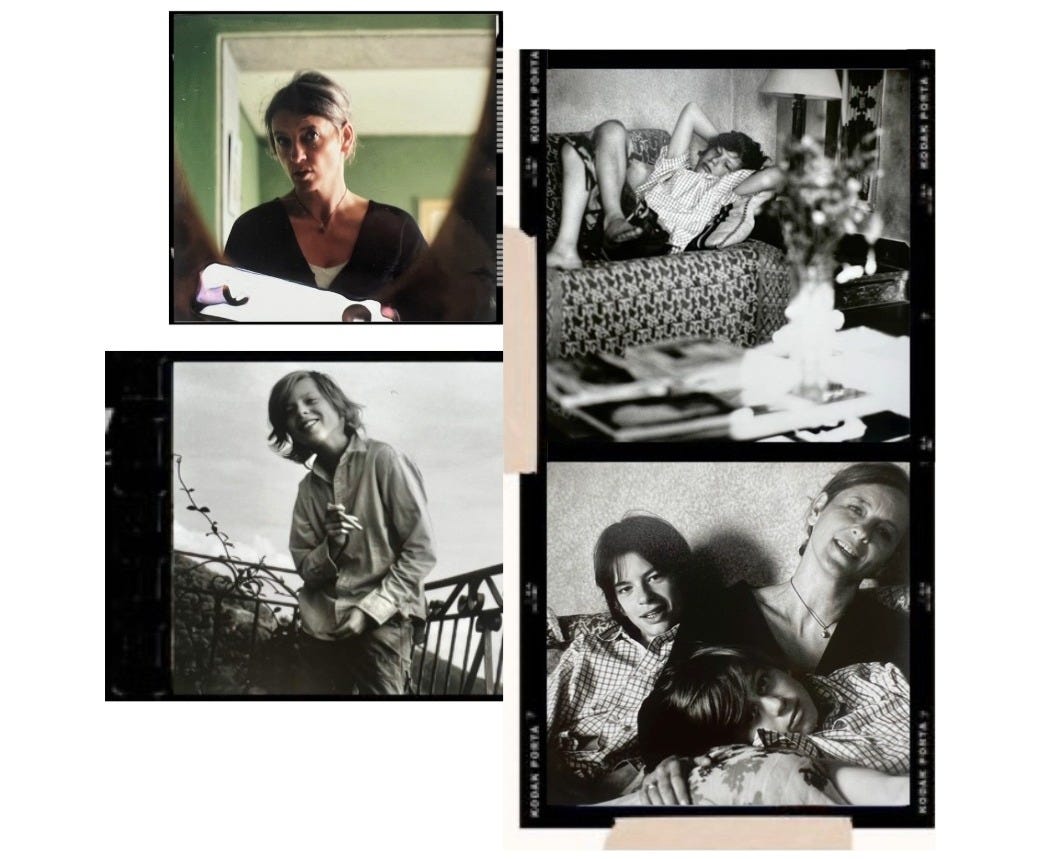

Born in Trieste in 1921 to a noble family, Fiore de Henriquez was a globe-trotting sculptor who became a British citizen. She worked between Italy, the U.K., and the U.S., known for expressive forms and celebrated portrait busts, among them J.F.K., Margot Fonteyn, Laurence Olivier, and the Queen Mother. Peralta was her “other work of art.” It was shaped by the eye, not plans. Built by hands, not machines.

Her sculptures are dotted around the property, unobtrusively positioned just where they should be, as if they grew out of the rock they stand on. Enigmatic, just like her. Many of the works are conjoined or have paired heads, echoing her intersex identity—which she acknowledged long before gender was discussed widely. The rough texture of the Arabian Phoenix on one of the terraces is in striking contrast to a life-sized sculpture of a woman, blending tenderness with fertility. One ready to soar, the other firmly grounded.

We were preparing dinner at Fiore’s Studio, our house for the week, when HJ, our youngest son, said he wasn’t hungry. That’s a red flag. Eleven-year-olds are always hungry. He didn’t eat. The next morning he skipped breakfast. That’s a siren blaring.

I popped into Fiore’s house and asked her for the nearest doctor. She suggested going straight to the hospital in Camaiore. An hour later, he was being prepped for surgery, disinfectant sharp in the air.

Around lunchtime, we found him in a double room, groggy and bewildered. There was an Italian boy his age in the bed next to him. And his mother, his father, what looked like four grandparents and two aunts fussing over his pillows, toys that would fill an entire aisle of a then-still-existing Toys “R” Us, and a folding bed propped up in the corner, still in its plastic wrapping.

We brought his book. Gave him a quick peck on the cheek. And left for lunch.

If looks could kill, we’d have been mincemeat. Parenting in Italy is a family business.

We went back to Peralta recently and spent a few more days at Fiore’s Studio. The granite doorstep hadn't moved, even as cars got wider. The property smelled of jasmine and thyme. The sculptures were more compelling than ever, more Houseago than we remembered. Clouds drifted up from the valley before it started to pour. Then the light returned: slates shimmering, puddles everywhere.

Peralta reset.

Only Fiore was missing, with a cigar in one hand and a whisky in the other, scowling. All woman and half a man. 1

Oh, about our son. He’s 33 now. Standing at six-foot-five. In perfect health. With an eight-centimeter scar on his abdomen.

And inspiring views on parenting.

https://www.aestheticnomads.com/

Contributors:

Hans Pauwels, words - Reinhilde Gielen, photographs

Artworks

Fiore De Henriquez, Peralta, Italy

Locations:

Peralta Tuscany, Peralta, Italy

Jan Marsh, The Guardian, 4th of August 2001

What a story — and what a setting to attach it to. Peralta sounds like the kind of place that imprints itself on a family whether it means to or not. The scar, the lunch break, the bewildered Italian nonni brigade… it’s unforgettable.

And Fiore — good grief. A person who could sculpt a place into existence and then haunt it in the best possible way. I felt like I was right there with the jasmine, the stone, the switchbacks that should come with a warning label.

Beautifully told and illustrated. This one lingers.

💛 Kelly

I love the layouts of your pictures (and your pictures of course 😍)