The United Jack Russell Kingdom

Mr Watson's Sidewalk Diaries #7 — Devon, Blake, & the Art of Never Arriving

Let’s hit the kill switch on 2025.

It’s been a year of friction; illustrious for some, devastating for others. If progress truly finds its origin in conflict, the future is going to be so bright we’d better wear shades.

I’ve always preferred the company of animals—four legs and a tail usually suggest a superior moral compass. Except sheep, perhaps. Mr. Watson and I are united in our stance on ovine objectification: he sees them as high-speed sport, I see them as a succulent, slow-roasted shoulder.

As the scent of rosemary and fat rises from the oven, I’ll let him have the last word of the year.

Happy New Year. May your 2026 be bright.

(And may Timbuk 3’s cynicism be misplaced.)

My first journey headed south. I was ten weeks old. My humans, R and H, had one of their brilliant ideas: let’s drive to Andalusia. Two thousand kilometers on R’s lap in a sports car. Holding my pee was still a work in progress. Especially on bumpy roads.

And in Madrid. The warm feeling I gave her didn’t last long.

I should have known that my wandering wasn’t going to end in Granada. Twenty hours in airports and Iberia planes to reach Uruguay put real pressure on a small bladder. Emptying it on three legs against Montevideo’s nearest pillar took ten minutes and gave me cramps in my left thigh.

Since then I’ve learned to negotiate better travel terms: back to my roots, the United Jack Russell Kingdom.

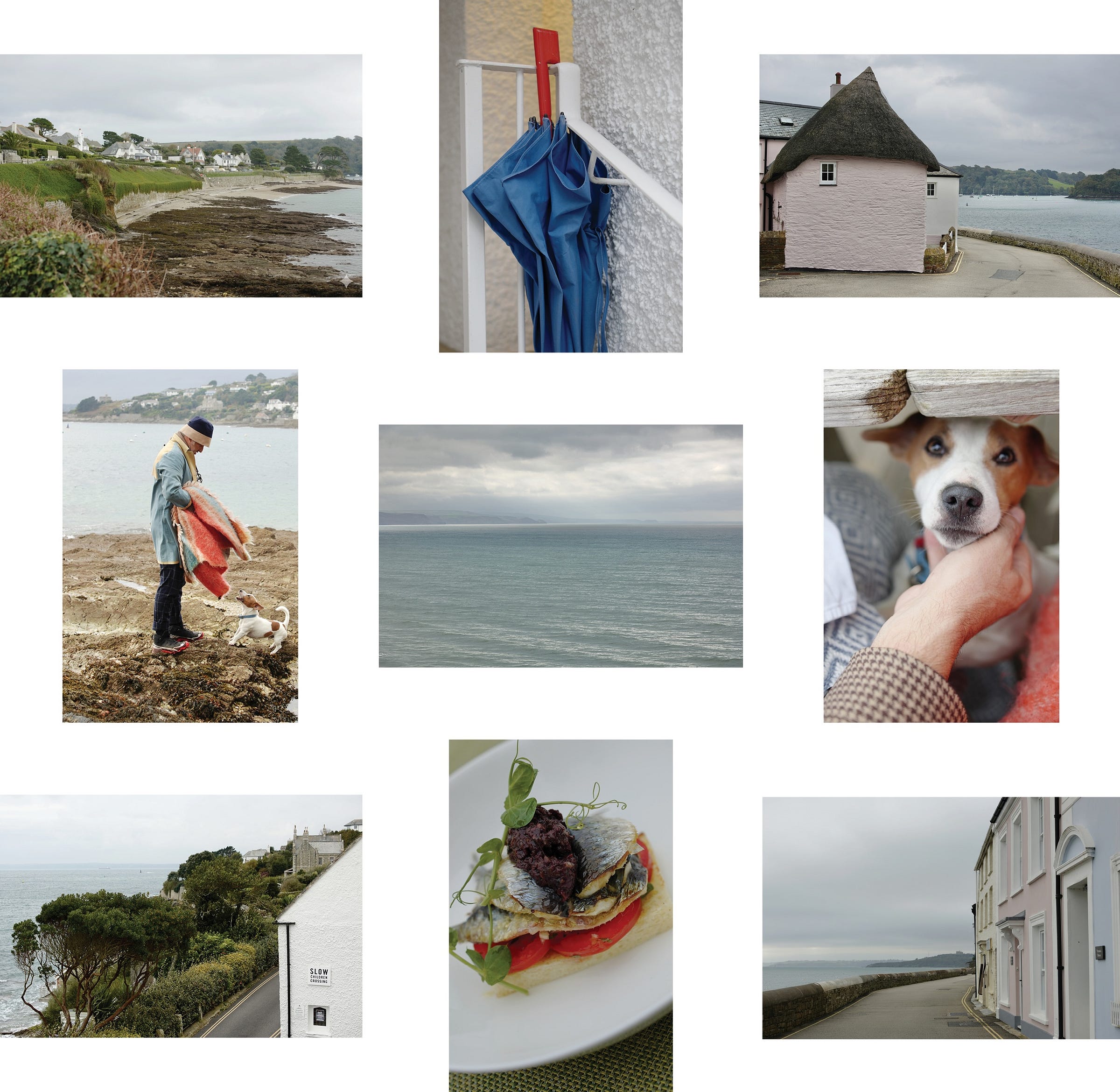

Devon, specifically. Fox-hunter by birth, tennis-ball retriever by conditioning. Sticks, as required by countryside statutes. An observer of the human comedy. Holy Pooch, they’re entertaining. More on them later.

We returned after five years when humans barricaded themselves from a collective sneeze, hid behind their computer screens, and covered their faces with unsightly paper contraptions that only delighted those with overdue dental appointments. In the equally collective mania of smoldering insular pride, the kingdom decided to redraw its friendships across the Channel, forgetting—momentarily—that its empire had disintegrated three generations ago. Paperwork grew teeth. I could be locked up in a pet crate for the wrong stamp. R and H, for a missing vaccine.

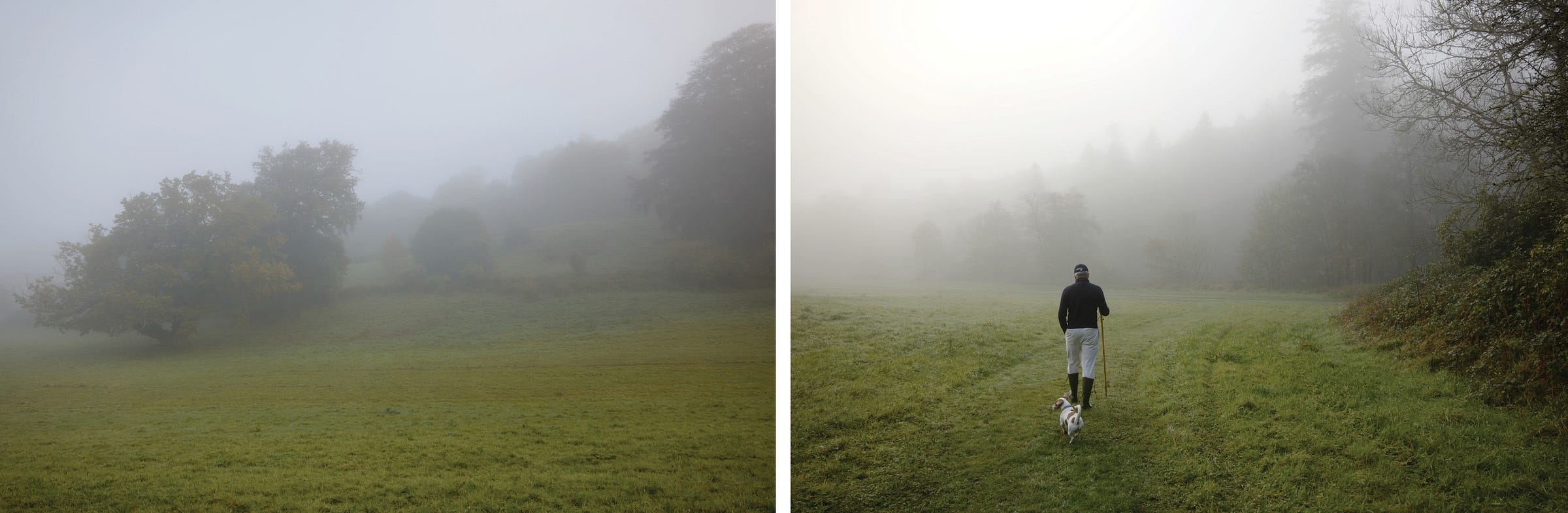

But we made it to my mountains green.

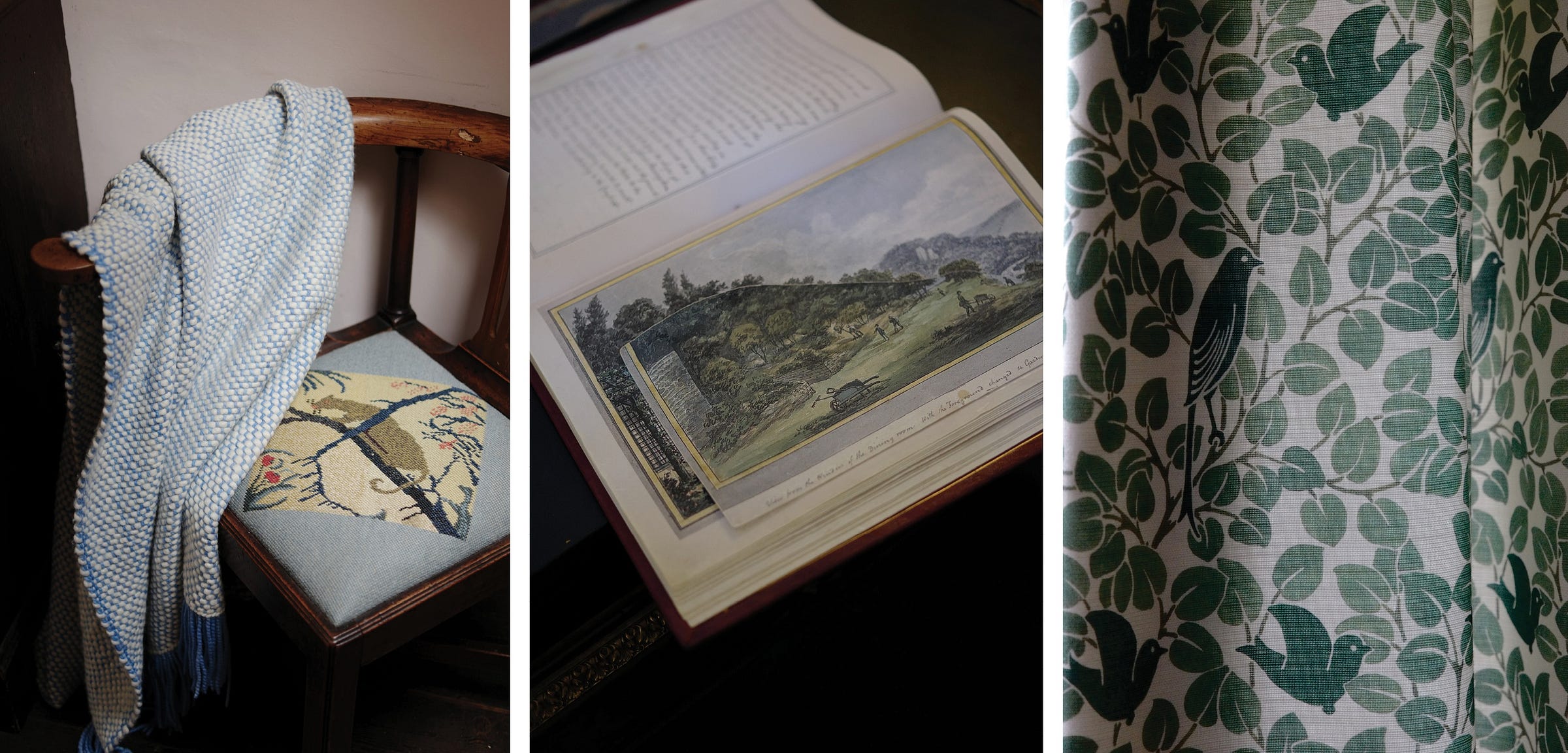

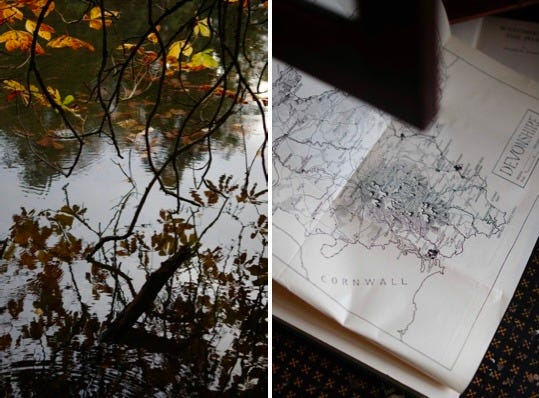

We took quarters with the Landmark Trust at Endsleigh: slate roof, steps slick with moss, and a pond so clear I had trouble tearing myself away from my reflection. No nymph required to boost my self-esteem. Huge “rhubarb” too. The kind that suggests a wild boar could part the leaves any minute. I’d growl if I weren’t frightened out of my senses.

Foxes are my size class. Smart, too.

Sheep are not. More wool than wits, even after shearing. And there are plenty on the moors, menu as much as sport.

Not convinced sheep are dimwits? Go to Greece around Easter for kefalaki—sheep’s heads, roasted or stewed. A plated countenance divine, if I ever saw one. Their eyes are bigger than their brains. And tastier, apparently. Can’t wait to pop one between my molars like wax candy. Fat chance; translucent sheep eyes are to Greeks what garlicky snails are to the French.

But on England’s pleasant pastures green, these future wall-to-wall carpets are my greatest playmates. I chased them over the hill, disappearing over the peak in full pursuit. Get one running and they all follow. Me grinning like a psycho on a field day when I returned twenty minutes later—sheep exhausted, me just getting warmed up. R and H blamed each other’s lousy dog-parenting instead of playing along. I, apparently, could have been shot by an angry farmer seeing his woolly Dollys in a mad downhill dash rather than tediously munching clover, adding fat to their rumps and value to his inventory on the hoof.

There’s not a mile of straight road in Devon. We searched for days.

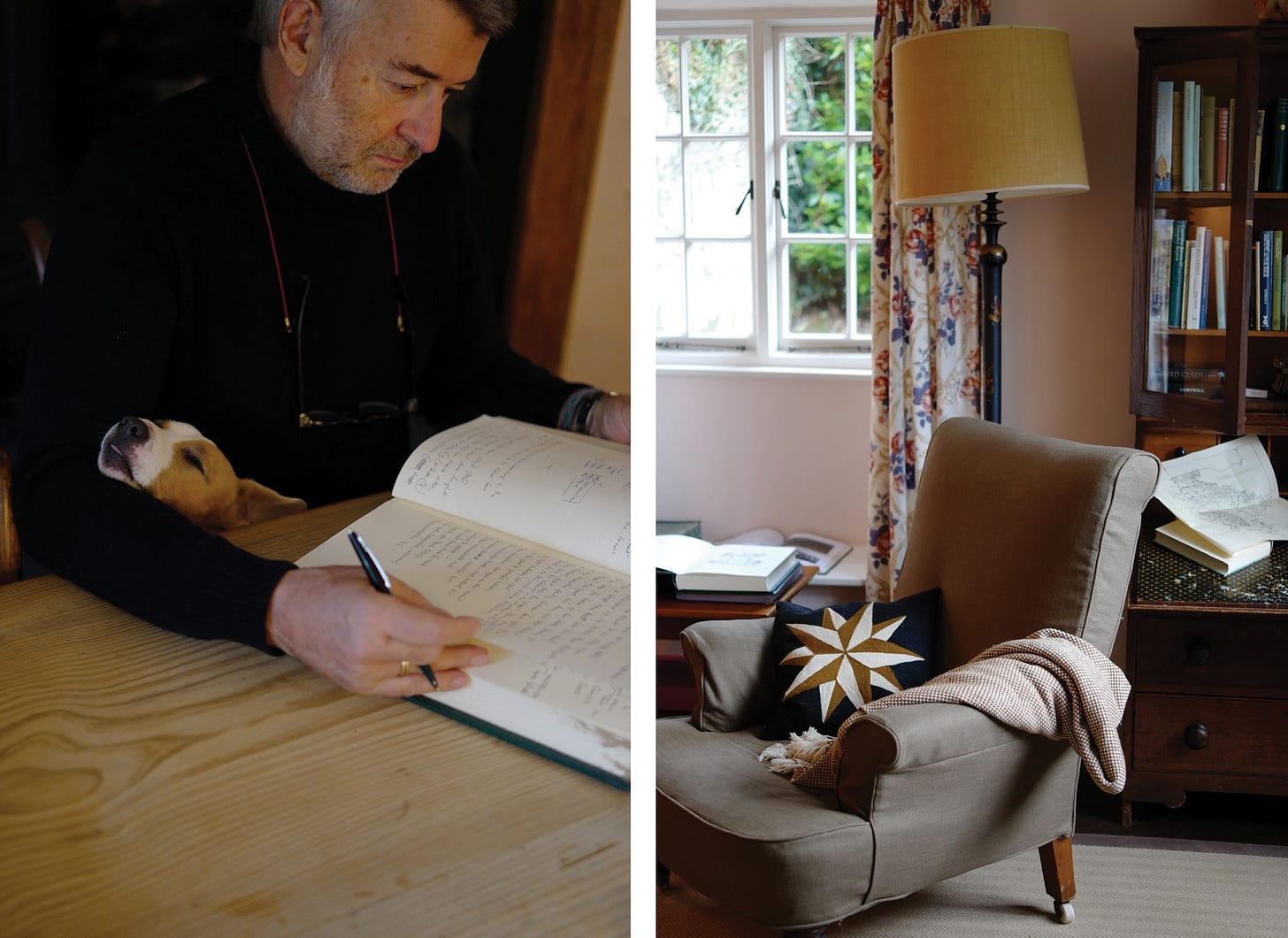

I discovered the method to my humans’ trajectory madness. First, they decide where to go. It’s a democratic process; the strongest always wins. So R decides and H drives. For him, the journey between two points is linear: you go from A to B by the optimal route.

That lasts until R sees the sun break through and set an old oak ablaze. Or a lane with clipped hedges on either side. A farm-shop sign; a field with corrugated-iron pig arks and the thought of bacon setting salivary glands to work; or a road sign for Frenchbeer, for the name’s sake. All justifications to veer off the track ingrained in H’s hunter focus (though he’s never hunted anything except hypothetical girlfriends in his youth, mostly without success—except for those desperate enough to prefer him over getting blasted, or those so plastered they hit on him).

R’s instructions reach him half a mile after the turn-off.

Information that demands disproportionate processing. We’re three miles down the road before the directive finally takes effect. H swings the car around, stamps the accelerator, and grumbles that Ugborough will be exactly what it sounds like: a lifeless commuter village with mail-order high-vis vests and a pub that closes on a Sunday afternoon.

R is mostly right, though. Maybe not about Ugborough. So right we never arrive at our destination. But end up everywhere else.

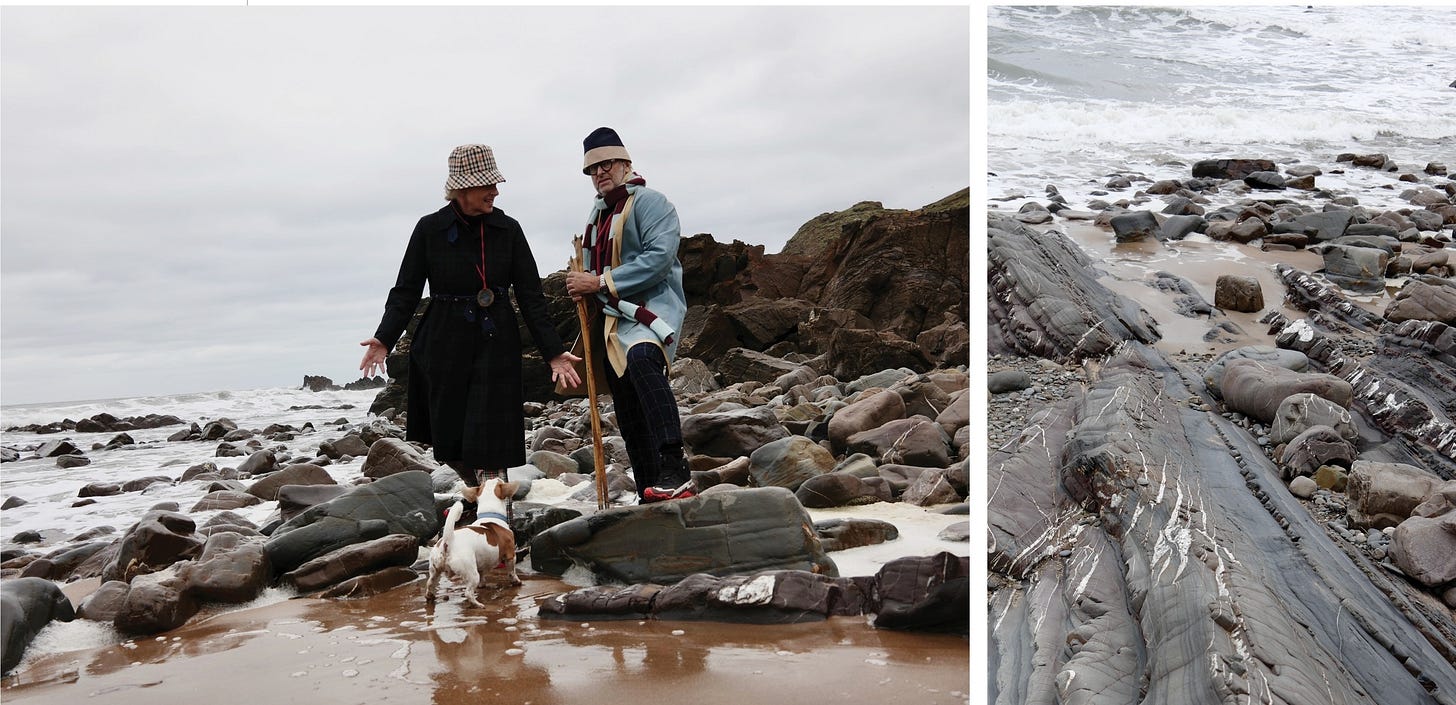

Like leaving Devon for Cornwall. And St Mawes. Swapping sheep for mackerel.

Thanks to my diminutive presence, this means lunch outside on a terrace, autumn clouds drifting in from the bay, and the wind shifting. R and H are cold; I’m comfortable on a lap under the table, beneath a warm mohair blanket. Anyone in a high-vis vest would be as rare as hen’s teeth. R knows where to deploy her mohair.

The sun breaks through as we approach Endsleigh again. No detours on our way back. No grumbling. No bouncing the rev limiter in frustration with whatever testosterone remains in men of his age.

As we arrive, horse trailers are hitched to Range Rovers that have yet to see the first speck of mud. Steam rises from beneath the horses’ intricately stitched blankets. Grooms stroke their flanks and tap their wet necks in reward, peeling off splint boots caked with mud. I hear dogs: beagles, distant cousins that never made it beyond the airport arrival halls, sniffing Samsonites for actions better left unreported. Or dirty laundry.

The hotel bar is a tide of leather riding boots and scarlet brass-buttoned jackets; I’m reflected in each, or the ceiling’s plasterwork in those with embonpoint. There’s a faint whiff of sweat and layers of Dior Sauvage. Leather wax too. But gin and tonic hits my nose more intensely than a recent squirt of a fox’s violet gland.

Logs roar. A sheepskin. I curl up and doze off. Perfect, if only it still had legs.

Bring me my bow of burning gold

Bring me my arrows of desire

Bring me my spear—O clouds unfold!

Bring me my chariot of fire.1

Let’s cut the giant rhubarb first. Wild boar can wait. Wet slate, gin in the air, beagles out of sight.

My kingdom is under consideration, eyes closed, legs twitching.

https://www.aestheticnomads.com/

Contributors:

Hans Pauwels, words - Reinhilde Gielen, photographs

Locations:

Endsleigh Estate & Hotel, Endsleigh, Devon, England

Pond Cottage, The Landmark Trust, Endsleigh, Devon, England

Hotel Tresanton, St Mawes, Cornwall, England

Blake, William. “Jerusalem”. Milton, a Poem. Around 1804.